DOI:https://doi.org/10.56669/NJEU3888

ABSTRACT

The current regulatory mechanisms associated with the development, production and commercialization of plant health promoting microorganism based products for managing plant health in India are very important issues. The interplay of different legislations, current challenges and gaps, and the required modifications for promotion and adoption of biopesticides are suggested. This review article focuses on the uses, commercialization, and adoption issues of various products in sustainable disease management.

Keywords: Biopesticide; commercialization, plant health promoting microorganism, IPM

INTRODUCTION

Ensuring food security is a principal goal of the Government of India after the Independence. Successful combination of improved technologies, policy support, and outreach programs helped India to achieve Green Revolution in the 1960’s. The technological implications resulted from high yielding varieties of wheat and rice (through targeted breeding approaches), chemical inputs in the form of fertilizers and pesticides, supported by expansion of irrigation projects and credit facilities were the main pillars of green revolution. However, increased food production was associated with chemical inputs carrying great environmental costs, such as low soil fertility, ground water contamination, and human health hazards. Moreover, there is a need for agriculture innovation to sustain current food production under the climate change and increasing population. For this, a “renewed” green revolution or bio-revolution is needed based on sustainable agriculture and ecofriendly inputs. This bio-revolution could be loosely based on the utilization of phyto-microbiome and improved climate smart cultivars. The microbial products are non-toxic, environmentally friendly and act as potential tools for plant growth promotion and disease control. Thus, the biological potential and fertility of soil could be increased, while the hazardous effects of agrochemicals could be decreased by neutralizing the agricultural crops with microbial agents. The great green revolution was possible because of the free exchange of diverse germplasm among the countries, however, at present, there are strict regulations for accession of any kind of biological entities (plant/animal/micro-organism) and their utilization. Currently, utilization of microorganisms for crop health is much needed in the form of commercial products, i.e., nutrient suppliers, disease and pest control agents to minimize chemical loads in the environment. Hence, India needs a clear, pre-defined regulatory mechanism to create a smooth path for commercialization of these products. The use of biopesticides become more relevant in the current scenario, as “natural farming” is gaining attention worldwide including India as it uses natural components to produce food, feed, and fiber. Thus, this chapter will discuss the current regulatory mechanisms associated with commercial production of bio-formulated products for managing plant health, and the regulatory requirements for better adoption and diffusion in the near future.

However, a lot of changes have occurred in the fertilizer and pesticide industry besides the enactment of legislations to regulate biofertilizers, biopesticides and biostimulants production.

HISTORY OF BIOPESTICIDES IN PEST MANAGEMENT

In the Integrated Pest Management (IPM) program, management of insect pests, diseases, weeds as well as plant growth must be considered in totality. The use of chemical pesticides, no doubt has led to greatly increased productivity and in turn provided a reliable supply of cheap food, so their use was initially welcomed. Recently, consumers have become increasingly concerned about food quality and the real and perceived effects of modern farming methods on a rapidly deteriorating environment. While many concerns have been exaggerated, there is a consensus that farming based on modern petrochemical inputs is ultimately unsustainable. As a result, more ecological approaches for enhancing the food production and quality are now being researched. Concurrently, research efforts are focusing on the use of traditional practices e.g., crop rotation, inter- and mixed cropping, organic amendments, summer ploughing, etc. Many of these practices are also successful in managing pests and diseases. Therefore, efforts were also initiated to integrate these practices in improving the disease management in farming system. The role of microbes in sustainable agriculture has provided new visions to agro-economy, and one of the direct benefits is the reduced reliance on chemical fertilizers and pesticides as the continuous application of these chemicals not only showed deleterious effects on agro-ecosystems but also resulted in health risks to humans and animals. Consequently, the use of microbes based on specific formulations to targeted pathogen offer an ecologically sound and effective solution to any diseases. They pose less of a threat to the environment and to human health. The advantages of using microbial-based formulations (instead of chemicals) are based on the following factors: (i) Ecological benefit: inherently less harmful on the environment; (ii) Target specificity: designed to affect only one specific disease, insect pest or a few target organisms; (iii) Environmental benefit: often effective in very small quantities and often decompose quickly, thereby resulting in lower exposures and largely avoiding the pollution problems; and (iv) Suitability: microbial-based formulations can contribute a great difference when used as a component of IPM programs.

Biofertilizers

Biofertilizers refer to preparations of plant growth-promoting microorganisms containing nitrogen fixing bacteria, phosphate solubilizing bacteria and fungi, mycorrhizae, etc., used to solubilize/mobilize nutrients to improve plant nutrition and promote plant growth. Their roles include improving crop yields, crop nutrition, mitigating adverse effects of biotic and abiotic stresses, improving soil fertility, nutrient use efficiency, water use efficiency, quality traits and availability of nutrients in soil or rhizosphere (Tarafdar, 2019; Rakshit et al., 2021).

The Ministry of Agriculture, Government of India brought biofertilizers and organic fertilizers under Fertilizer Control Order (FCO) in 2006. The recent draft of Plant Bio-stimulants Order issued by the Government of India includes microorganisms in the definition but does not list any of the 10 microbial agents currently classified by FCO as biofertilizers. In the context of the FCO itself, considering the overall mechanism of action, India should include some of the biopesticides (Pseudomonas, Bacillus, Trichoderma) under FCO’s biofertilizer lists as what has been done in USA and Canada for these organisms since they are also known to improve nutrient use efficiency (Reddy et al., 2021;Singh and Vaishnav, 2021;Singh and Vaishnav, 2022).

In India, plant growth promoting microorganisms are categorized as ‘biofertilizers’ when registered under fertilizer legislations and as ‘Biopesticides’ when registered and regulated under the plant protection category. In Europe and USA, Biofertilizers and some Biopesticides are categorized as Microbial Plant Biostimulants since they are more similar to fertilizing products than plant protection products.

Biopesticides

In the last few years, the development of microbial biopesticides to enhance plant growth and eradicate diseases has emerged as an alternative, but a broader aspect of their application as stimulant products has remained in infancy especially in developing countries. On an economic and social level, this climate friendly strategy also faces many hurdles and lags far behind its competitors, synthetic fertilizers and pesticides. Most of the time, it has been found that bio-formulations available for a particular crop do not work as well in field as they do under laboratory conditions. Various researchers all over the world are continuously engaged in developing bio-formulated products that are easier to use, with enhanced activity against plant pathogens, and potentially covering more target crops. The whole process of bio-formulation development from microbe screening to product development and its implementation need to be reviewed. Microbe-based formulations also known as biopesticides are more robust than synthetic chemicals as the formulation product of a single microbe may involve direct interactions with pathogens, and many mechanisms take part in disease suppression and plant growth promotion (Singh et.al., 2016).

In India, biopesticides is regulated under the Insecticides Act 1968. Any microbial strain developed or sold for pest and disease control ought to be registered with the Central Insecticide Board (CIB) of the MOA. Manufacturers of biopesticides can register their products temporarily or regularly under section 9 (3) and 9 (3b). The temporary registration is less stringent than regular registration, thereby reducing commercial barriers for product development (Singh et.al., 2016).

Biostimulants

The Farm Bill 2018 of USA describes biostimulants as “a substance or micro-organism that, when applied to seeds, plants, or the rhizosphere, stimulates natural processes to enhance or benefit nutrient uptake, nutrient efficiency, tolerance to abiotic stress, or crop quality and yield.” Here microbial biostimulants broadly specify: Rhizobium, PGPR, Mycorrhizae, Trichoderma and other beneficial fungi (Singh and Vaishnav, 2021;2022). This brings within the ambit of microbial plant biostimulants, organisms such as Trichoderma, Bacillus and Pseudomonas (allowed so long as a plant protection claim is not made on their product label). Biostimulants can also include much more complex “natural” communities derived from organic matter processing. Biostimulants are regulated as microbial supplements in Canada under the Fertilizers Act. Many products offer both crop fertilization and crop protection traits. Under the current Canadian regulations, manufacturers must choose whether their products are regulated under the Fertilizers Act or the Pest Control Products Act. Both properties of nutrient supplement and health control cannot be claimed on the same label. There is a need to develop a process that would allow for dual registration on a single label to be evolved. Azotobacter spp., mycorrhizal fungi, Rhizobium spp. and Azospirillum spp. are approved so far in the EU legislation on plant microbial biostimulants. Only these four organisms will be currently regulated, while a number of innovative products (such as consortia of microorganisms) are omitted, and manufacturers are not allowed to produce and sell them. It is a serious restriction, and it may be noted that fortunately India has an approved NPK consortium in the FCO (Reddy et. al., 2021).

The list of microorganisms considered as plant biostimulants varies from country to country. Some include only biofertilizers and some include biopesticides, with or without label claims. In India, the biofertilizers and biopesticides are distinctly defined and regulated. Furthermore, the understanding of the definitions of biofertilizers and biopesticides are different in different countries. The EU and USA define them only based on their physiological effects on plants rather than their compositions, while India define them based on their inherent functionality of microbes.

Table 1. Representative list of biofertilizers, biopesticides and biostimulants regulation in the world

|

Particulars

|

Biofertilizers

|

Biopesticides

|

Plant microbial biostimulants

|

|

Examples of technologies developed/ commercialized microorganisms

|

Rhizobia; Azotobacter; Azospirillum; Phosphate solubilizing fungi; mycorrhiza; blue green algae, etc.

|

Trichoderma viride,

T. harzianum, Pseudomonas fluorescens

|

India: Specific microorganisms are not yet listed.

Europe: Azotobacter spp., Mycorrhizal fungi, Rhizobium spp. and Azospirillum spp.

USA: Rhizobium, PGPR, Mycorrizae, Trichoderma, Bacillus, Pseudomonas, other beneficial fungi.

|

|

Acts and rules (Specific to products)

|

Fertilizer (Control) Order, 1957/1985; Fertilizer (Movement Control) Order, 1960/1973; ECA Allocation Orders; FCO 2006/ 2009

|

Insecticides Act 1968; Insecticides Rules 1971; Pesticide Management Bill 2008

|

The Gazette of India Order dated 23rd February, 2021

|

|

Acts and rules (common to PGPR and other biologicals)

|

The Essential Commodities Act, 1955; The Biodiversity Act, 2002; The Seeds Act 1966; The Bureau of Indian Standards Act 2016

|

|

Nodal ministry/ Agency

|

Ministry of Agriculture

|

CIBRC under MOA

|

|

|

Role of Central Government

|

(i) Enactment and amendment of Acts and Rules from time to time; (ii) Registration of new chemical/ biofertilizers; (iii) Registration of industrial dealers; (iv) Ban/ restriction on use of registered products from time to time; (v) Allocation orders.

|

(i) Enactment and amendment of Acts and Rules from time to time; (ii) Registration of new chemical/ biopesticides; (iii) Ban/ restriction on use of registered products from time to time.

|

|

|

Role of State Governments

|

Enforcement: (i) Registration of manufacturers, importers and dealers; (ii) Production and distribution; (iii) Quality control (Fertilizer Inspector); (iv) Punitive actions for violation of provisions.

|

Enforcement: (i) Registration of manufacturers, importers, and dealers; (ii) Production and distribution; (iii) Quality control (Insecticide Inspector); (iv) Punitive actions for violation of provisions.

|

|

LEGISLATIONS ON BIOFERTILIZERS AND BIOPESTICIDES

The Biological Diversity Act, 2002

This Act regulates the accession and use of biological materials, development of biological based technologies/products and their patents, commercialization, equitable benefit sharing and licensing for commercial use in India and abroad by domestic and foreign organizations and nationals within India. The microorganism utilized for plant growth promoting microorganism manufacturing must be registered under this Act.

The Bureau of Indian Standards Act, 2016

This Act regulates the quality of goods and products through standard conformity and quality assurance. The Bureau of Indian Standards is the national standards body for standards formulation and certification marks.

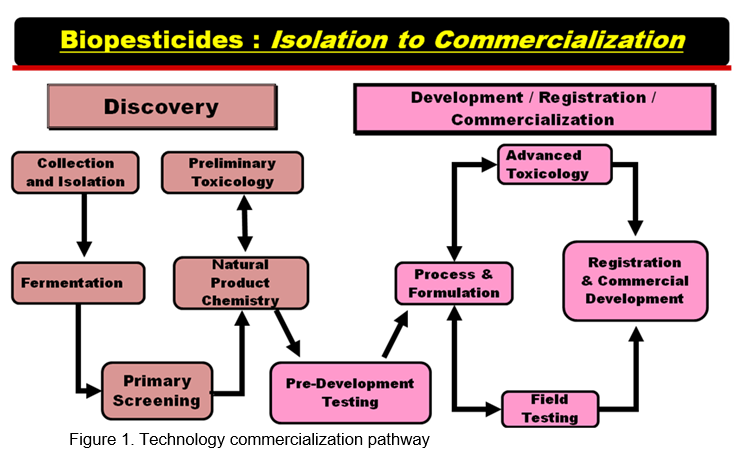

COMMERCIALIZATION: IS IT A CHALLENGE IN THE FIELD OF BIOPESTICIDES?

The commercialization of biopesticides is a multistep process. Although it is easy for any research organization to identify any region-specific strain of biocontrol agents, it becomes quite difficult to bring them up to the level of commercial production. Because, any biocontrol agent has to undergo the same registration processes as any chemical pesticide, which is quite cumbersome, time-consuming and costly. Since there is no stability in the effect of biopesticides, farmers always had doubts. Again, due to the living nature of microbial biopesticides, several factors such as temperature, moisture, pH, ultraviolet spectrum, and soil factors can adversely affect their survival. Dealers and retailers are also least encouraged to promote biopesticides due to the short shelf-life of the products, low profit margins and lack of overall demand from farmers. All these together have resulted in limited adoption of biopesticides by farmers. However, in recent decades, the diffusion and use of natural and eco-friendly products for pests, diseases and nutrient management in agriculture has increased in India due to several reasons:

Climate change and sustainability

Climate change poses a threat to agriculture and livelihoods at the global level and India is one of the most affected countries owing to its huge population which is dependent on agriculture. Excessive and exploitative use of non-renewable resources such as petroleum products (for the production of chemical fertilizers and pesticides) is also a contributing factor to climate change.

Self-sufficiency in food production

India has attained self-sufficiency in grain production since the 1980s. This has enabled India to shift its focus to the quality of food production while sustaining the quantity of current level of food production. India’s current agricultural policies aim to achieve sustainable management of natural resources, sustainability of agriculture, enhancing farm incomes and eradicating malnutrition. Eco-friendly and green technologies are being promoted to gradually replace/ reduce chemical intensive agriculture.

Increasing awareness among consumers

Increasing quality of life and income levels has enabled urban population to be more aware of the quality of food products they consume. Healthy foods and lifestyles have become a priority, diverse, and chemical-free foods are sought after by this section of the society.

Increase in area under organic/ chemical-free agriculture

There is an increase in area under organic agriculture in India, which again illustrates the shift towards reduction in use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides as practiced in intensive agriculture. The total area dedicated to organic agriculture in Asia exceeded 5.9 million hectares in 2019. There were 1.4 million producers, most of them are in India. The leading countries by area were India (2.3 million ha) and China (over 2.2 million ha). With only 1.3% of total agricultural land under organic agriculture, India stands fifth among countries with the largest organic agricultural land area in 2019 at the global level (Hossain et al., 2021).

In India, a major technological breakthrough in biocontrol happened when chemical insecticides failed to control Helicoverpa armigera, Spodoptera litura, and other pests of cotton (Kranthi et al., 2002). It was realized that biocontrol is the safest, cost-effective, and eco-friendly method to control the widespread resistance of pests to chemical insecticides. Later, biopesticides became part of IPM which was previously completely based on the use of chemical pesticides (Misra et al., 2020) In this context, biopesticides play an important role in the promotion of eco-friendly and organic agriculture.

STATUS OF COMMERCIALIZATION, REJECTION AND ADOPTION OF BIOPESTICIDES BY THE FARMERS IN INDIA

In India, as of 2008, 15 biopesticides were registered under the Insecticides Act (1968), and their market share is only 4.2% of the overall pesticide market. However, it is predicted to increase at an annual growth rate of 10%. There are around 400 registered biopesticide active ingredients and over 1,250 actively registered biopesticide products in Indian markets (Anonymous, 2021). It shows the awareness among the farmers as well as policy support of the government to use the ecologically safe products for pest management. There are 970 biopesticide registrant companies in India by 2020 (Anonymous, 2021). However, the commercialization and adoption of the biopesticides in India is still low on account of several reasons:

- Lack of awareness on its technical know-how and use;

- Low demand and production of the biopesticides;

- Lack of consistency in performance;

- Regulatory requirements;

- Quality control;

- Valuation and pricing of the technology; and

- Cost of biopesticide unit.

TECHNICAL, LEGAL AND POLICY ISSUES ON NEW PRODUCT REGISTRATION

Even now, the guidelines for registration of biopesticide products draw too heavily on those for chemicals. In some cases, it is requested to supply information that is only relevant to chemical products and not biological products. A biocontrol preparation may sometimes aim at a small market. Being a live entity makes the biocontrol agent unique among control agents, which are usually chemical pesticides. A biocontrol agent is more affected by microclimate factors, and may need different attention regarding shipment, storage, and use. Potential users and distributors should be educated about its handling and need to be convinced about the value of a biocontrol product, which is somewhat more difficult to use than standard pesticides. Thus, adoption of these technologies by growers proceeds more slowly than expected. Indeed, in many places, farmers, agricultural advisors and even researchers and field personnel were not accustomed to the special handling and use demands that are imposed by the live biocontrol agent. Therefore, special instructions for biopesticide use had to be formulated and then had to be delivered along the chain of marketing, sales, and implementation.

During the more than last five decades, the area under bio-intensive IPM remained below 3% with biopesticides constituting only around 3% of pesticide market in the country. Present volume of around 27,000 tons of licensed production of registered biopesticides is a miniscule quantity for a large arable area of 142 million hectare in India. Nevertheless, biopesticides cannot qualify as alternatives to chemical pesticides, but can serve as an important component of disease management. Recently a gazette notification was released about the use of biocontrol agents where some of the genera of biocontrol agents were recently notified as biostimulants by GOI (Gazette Notification 2021). Therefore, chronic toxicology tests may not be required for these formulations, to enable easy and speedy registration of these bio-products.

FUTURE PROSPECTS

The establishment of a certification process to ensure the efficacy, quality, and consistency of biocontrol products would improve the global market perception of biopesticides as effective products. Data should be in the public domain and easily available to the farmers and extension workers. The effectiveness and safety of biocontrol products are essential for their successful commercialization. Farmers have to be educated that plant diseases have to be managed rather than completely controlled and that biologicals are an important part of the integrated pest management. Private companies are reluctant towards biocontrol R&D owing to limited market size, product inconsistency, and present methods of production, formulation and distribution. Recent advances in genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics can guide the development of next-generation bio-formulations with longer shelf-life.

REFERENCES

Anonymous (2021). Bio-pesticide registrant. Central insecticides Board and Registration committee,Directorate of Plant Protection, Quarantine and Storage, Department of Agriculture, Cooperation andFarmers Welfare, (CIB&RC) Government of India. http://ppqs.gov.in/divisions/cib-rc/biopesticideregistrant. Accessed 20Mar 2021

Arjjumend H, Koutouki K (2020) Legal Barriers and Quality Compliance in the Business of Biofertilizers and Biopesticides in India. J Legal Studies 26(40): 81-101.

Bhide R (2013) Regulatory perspective of agrochemicals in India, Agro News, July 19, 2013. Retrieved from http://news.agropages.com/News/NewsDetail-10045.htm

Kandpal V (2014) Biopesticides, Int J Environ Res Devl 4(2): 191-196.

Hossain ST, Chang J and Tagupta VJF (2021). Developments in organic sector in Asia in 2020 p198-2015. In Proceedings : The world of organic agriculture - statistics and emerging trends 2021, (Eds: Willer et al) Research Institute of Organic Agriculture FiBL, Frick, Switzerland and IFOAM Organics International, Bonn, p.340

Kranthi KR, Russell D, Wanjari R, Kherde M, Munje S, Lavhe N, Armes N (2002) In-season changes in resistance to insecticides in Helicoverpa armigera (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in India. J Econ Entomol 95(1): 134–142. https://doi.org/10.1603/0022-0493-95.1.134

Kumar V (2020) Union Budget 2020-21: Big talk on natural farming but no support. Down to Earth, 3 February 2020. Available at: https://www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/agriculture/union-budget-2020-21-big-talk-on-natural-farming-but-no-support-69131

Manjunatha BL, Hajong D, Tewari P, Singh Bhagwan, Shantaraja CS, Nikumbhe PH, Jat NK, Shiran K, Parihar RP (2018) Quality Seed Accessibility Index: A Case Study from a Village in Western Rajasthan. Indian J Ext Edu 54(1): 33-43.

Manjunatha B L, Rao DUM, Sharma JP, Burman RR, Hajong D, Dastagiri MB Sumanthkumar V (2015) Factors Affecting Accessibility, Use and Performance of Quality Seeds in Andhra Pradesh and Bihar: Farmers’ Experiences, J Community Mobil Sus Develp, 10(1): 130-145.

Mawar R, Manjunatha BL, Kumar S (2021) Commercialization, diffusion and adoption of bioformulations for sustainable disease management in Indian arid agriculture: Prospects and Challenges. Circular Eco Sustain p.19.https://doi.org/10.1007/s43615-021-00089-y

Mishra J, Dutta V, Arora NK (2020) Biopesticides in India: Technology and sustainable linkages. 3 Biotech 10(5): 210. doi: 10.1007/s13205-020-02192-7

MoA (2021a) Consumption of bio pesticides formulations in various states during 2016-17 to 2020-21, Directorate of Plant Protection, Quarantine and Storage, Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, GoI. Available at http://ppqs.gov.in/statistical-database. Accessed on 19/08/2021.

MoA (2021b) Bio-pesticide Registrant. Directorate of Plant Protection, Quarantine and Storage, Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, GoI. Available at http://ppqs.gov.in/divisions/cib-rc/bio-pesticide-registrant. Accessed on 19/08/2021.

Pathak DV, Singh S, Saini RS (2013) Impact of bio-inoculants on seed germination and plant growth of guava (Psidiumguajava). J Hort Forest 5(10):183-185.

Rakshit A, Meena VS, Parihar M, Singh HB, Singh AK (2021) Biofertilizers: Advances in Bio-inoculants. Volume 1. Elsevier p. 422.

Rakshit A, Meena VS, Abhilash PC, Sarma BK, Singh HB, Leonardo FracetoParihar M, Singh AK (2022) Biopesticides: Advances in Bioinoculants.Volume2 . Elsevier p.430.

Reddy MS, Rao DLN, Seshadri S, Krishna Sundari S, Sayyed,R.Z. (2021) Regulation of Plant Growth Promoting Microorganisms. Policy Paper No. 1., Asian PGPR Society, Auburn, Alabama, USA.

Sharma, K., Raju, S., Kumar, D. & Thakur, S. (2018). Biopesticides: an effective tool for insect pest management and current scenario in India, Indian Journal of Agriculture and Allied Sciences, 4(2), 59-62.

The Gazette of India. 2021. Order, Department of Agriculture, Cooperation and Farmers Welfare, Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, New Delhi, dated 23 February, 2021.

Singh, A., Jheeba, S. S.,Pramendra., Manjunatha, B. L. and Hajong, D. 2022. Adoption of chemical pesticides under commercial vegetable cultivation in Sri Ganganagardistrict of Rajasthan,Indian Journal of Extension Education, 58(1), 1-6.

Singh, H.B., Sarma, B.K. and Keswani, C. Eds. (2016). Agriculturally Important Microorganisms: Commercialization and Regulatory Requirements in Asia. Springer, Singapore p.305.

Singh, H.B and Anukool,Vaishnav. Eds. (2022). New and Future Developments in Microbial Biotechnology: Sustainable Agriculture: Microorganisms as Biostimulants. Elsevier p.374.

Singh, H.B and Anukool, Vaishnav. Eds.(2022). New and Future Developments in Microbial Biotechnology: Sustainable Agriculture:.Advances in microbe-based biostimulants. Elsevier p.457

Tarafdar, J.C. (2019) Fungalinoculants for native phosphorus mobilization. In: B. Giri et al. (eds.), Biofertilizers for Sustainable Agriculture and Environment, Soil Biology 55, Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-18933-4_

An Overview of Current Regulatory Requirements for Bio-pesticide for Sustainable Disease Management in Indian Condition

DOI:https://doi.org/10.56669/NJEU3888

ABSTRACT

The current regulatory mechanisms associated with the development, production and commercialization of plant health promoting microorganism based products for managing plant health in India are very important issues. The interplay of different legislations, current challenges and gaps, and the required modifications for promotion and adoption of biopesticides are suggested. This review article focuses on the uses, commercialization, and adoption issues of various products in sustainable disease management.

Keywords: Biopesticide; commercialization, plant health promoting microorganism, IPM

INTRODUCTION

Ensuring food security is a principal goal of the Government of India after the Independence. Successful combination of improved technologies, policy support, and outreach programs helped India to achieve Green Revolution in the 1960’s. The technological implications resulted from high yielding varieties of wheat and rice (through targeted breeding approaches), chemical inputs in the form of fertilizers and pesticides, supported by expansion of irrigation projects and credit facilities were the main pillars of green revolution. However, increased food production was associated with chemical inputs carrying great environmental costs, such as low soil fertility, ground water contamination, and human health hazards. Moreover, there is a need for agriculture innovation to sustain current food production under the climate change and increasing population. For this, a “renewed” green revolution or bio-revolution is needed based on sustainable agriculture and ecofriendly inputs. This bio-revolution could be loosely based on the utilization of phyto-microbiome and improved climate smart cultivars. The microbial products are non-toxic, environmentally friendly and act as potential tools for plant growth promotion and disease control. Thus, the biological potential and fertility of soil could be increased, while the hazardous effects of agrochemicals could be decreased by neutralizing the agricultural crops with microbial agents. The great green revolution was possible because of the free exchange of diverse germplasm among the countries, however, at present, there are strict regulations for accession of any kind of biological entities (plant/animal/micro-organism) and their utilization. Currently, utilization of microorganisms for crop health is much needed in the form of commercial products, i.e., nutrient suppliers, disease and pest control agents to minimize chemical loads in the environment. Hence, India needs a clear, pre-defined regulatory mechanism to create a smooth path for commercialization of these products. The use of biopesticides become more relevant in the current scenario, as “natural farming” is gaining attention worldwide including India as it uses natural components to produce food, feed, and fiber. Thus, this chapter will discuss the current regulatory mechanisms associated with commercial production of bio-formulated products for managing plant health, and the regulatory requirements for better adoption and diffusion in the near future.

However, a lot of changes have occurred in the fertilizer and pesticide industry besides the enactment of legislations to regulate biofertilizers, biopesticides and biostimulants production.

HISTORY OF BIOPESTICIDES IN PEST MANAGEMENT

In the Integrated Pest Management (IPM) program, management of insect pests, diseases, weeds as well as plant growth must be considered in totality. The use of chemical pesticides, no doubt has led to greatly increased productivity and in turn provided a reliable supply of cheap food, so their use was initially welcomed. Recently, consumers have become increasingly concerned about food quality and the real and perceived effects of modern farming methods on a rapidly deteriorating environment. While many concerns have been exaggerated, there is a consensus that farming based on modern petrochemical inputs is ultimately unsustainable. As a result, more ecological approaches for enhancing the food production and quality are now being researched. Concurrently, research efforts are focusing on the use of traditional practices e.g., crop rotation, inter- and mixed cropping, organic amendments, summer ploughing, etc. Many of these practices are also successful in managing pests and diseases. Therefore, efforts were also initiated to integrate these practices in improving the disease management in farming system. The role of microbes in sustainable agriculture has provided new visions to agro-economy, and one of the direct benefits is the reduced reliance on chemical fertilizers and pesticides as the continuous application of these chemicals not only showed deleterious effects on agro-ecosystems but also resulted in health risks to humans and animals. Consequently, the use of microbes based on specific formulations to targeted pathogen offer an ecologically sound and effective solution to any diseases. They pose less of a threat to the environment and to human health. The advantages of using microbial-based formulations (instead of chemicals) are based on the following factors: (i) Ecological benefit: inherently less harmful on the environment; (ii) Target specificity: designed to affect only one specific disease, insect pest or a few target organisms; (iii) Environmental benefit: often effective in very small quantities and often decompose quickly, thereby resulting in lower exposures and largely avoiding the pollution problems; and (iv) Suitability: microbial-based formulations can contribute a great difference when used as a component of IPM programs.

Biofertilizers

Biofertilizers refer to preparations of plant growth-promoting microorganisms containing nitrogen fixing bacteria, phosphate solubilizing bacteria and fungi, mycorrhizae, etc., used to solubilize/mobilize nutrients to improve plant nutrition and promote plant growth. Their roles include improving crop yields, crop nutrition, mitigating adverse effects of biotic and abiotic stresses, improving soil fertility, nutrient use efficiency, water use efficiency, quality traits and availability of nutrients in soil or rhizosphere (Tarafdar, 2019; Rakshit et al., 2021).

The Ministry of Agriculture, Government of India brought biofertilizers and organic fertilizers under Fertilizer Control Order (FCO) in 2006. The recent draft of Plant Bio-stimulants Order issued by the Government of India includes microorganisms in the definition but does not list any of the 10 microbial agents currently classified by FCO as biofertilizers. In the context of the FCO itself, considering the overall mechanism of action, India should include some of the biopesticides (Pseudomonas, Bacillus, Trichoderma) under FCO’s biofertilizer lists as what has been done in USA and Canada for these organisms since they are also known to improve nutrient use efficiency (Reddy et al., 2021;Singh and Vaishnav, 2021;Singh and Vaishnav, 2022).

In India, plant growth promoting microorganisms are categorized as ‘biofertilizers’ when registered under fertilizer legislations and as ‘Biopesticides’ when registered and regulated under the plant protection category. In Europe and USA, Biofertilizers and some Biopesticides are categorized as Microbial Plant Biostimulants since they are more similar to fertilizing products than plant protection products.

Biopesticides

In the last few years, the development of microbial biopesticides to enhance plant growth and eradicate diseases has emerged as an alternative, but a broader aspect of their application as stimulant products has remained in infancy especially in developing countries. On an economic and social level, this climate friendly strategy also faces many hurdles and lags far behind its competitors, synthetic fertilizers and pesticides. Most of the time, it has been found that bio-formulations available for a particular crop do not work as well in field as they do under laboratory conditions. Various researchers all over the world are continuously engaged in developing bio-formulated products that are easier to use, with enhanced activity against plant pathogens, and potentially covering more target crops. The whole process of bio-formulation development from microbe screening to product development and its implementation need to be reviewed. Microbe-based formulations also known as biopesticides are more robust than synthetic chemicals as the formulation product of a single microbe may involve direct interactions with pathogens, and many mechanisms take part in disease suppression and plant growth promotion (Singh et.al., 2016).

In India, biopesticides is regulated under the Insecticides Act 1968. Any microbial strain developed or sold for pest and disease control ought to be registered with the Central Insecticide Board (CIB) of the MOA. Manufacturers of biopesticides can register their products temporarily or regularly under section 9 (3) and 9 (3b). The temporary registration is less stringent than regular registration, thereby reducing commercial barriers for product development (Singh et.al., 2016).

Biostimulants

The Farm Bill 2018 of USA describes biostimulants as “a substance or micro-organism that, when applied to seeds, plants, or the rhizosphere, stimulates natural processes to enhance or benefit nutrient uptake, nutrient efficiency, tolerance to abiotic stress, or crop quality and yield.” Here microbial biostimulants broadly specify: Rhizobium, PGPR, Mycorrhizae, Trichoderma and other beneficial fungi (Singh and Vaishnav, 2021;2022). This brings within the ambit of microbial plant biostimulants, organisms such as Trichoderma, Bacillus and Pseudomonas (allowed so long as a plant protection claim is not made on their product label). Biostimulants can also include much more complex “natural” communities derived from organic matter processing. Biostimulants are regulated as microbial supplements in Canada under the Fertilizers Act. Many products offer both crop fertilization and crop protection traits. Under the current Canadian regulations, manufacturers must choose whether their products are regulated under the Fertilizers Act or the Pest Control Products Act. Both properties of nutrient supplement and health control cannot be claimed on the same label. There is a need to develop a process that would allow for dual registration on a single label to be evolved. Azotobacter spp., mycorrhizal fungi, Rhizobium spp. and Azospirillum spp. are approved so far in the EU legislation on plant microbial biostimulants. Only these four organisms will be currently regulated, while a number of innovative products (such as consortia of microorganisms) are omitted, and manufacturers are not allowed to produce and sell them. It is a serious restriction, and it may be noted that fortunately India has an approved NPK consortium in the FCO (Reddy et. al., 2021).

The list of microorganisms considered as plant biostimulants varies from country to country. Some include only biofertilizers and some include biopesticides, with or without label claims. In India, the biofertilizers and biopesticides are distinctly defined and regulated. Furthermore, the understanding of the definitions of biofertilizers and biopesticides are different in different countries. The EU and USA define them only based on their physiological effects on plants rather than their compositions, while India define them based on their inherent functionality of microbes.

Table 1. Representative list of biofertilizers, biopesticides and biostimulants regulation in the world

Particulars

Biofertilizers

Biopesticides

Plant microbial biostimulants

Examples of technologies developed/ commercialized microorganisms

Rhizobia; Azotobacter; Azospirillum; Phosphate solubilizing fungi; mycorrhiza; blue green algae, etc.

Trichoderma viride,

T. harzianum, Pseudomonas fluorescens

India: Specific microorganisms are not yet listed.

Europe: Azotobacter spp., Mycorrhizal fungi, Rhizobium spp. and Azospirillum spp.

USA: Rhizobium, PGPR, Mycorrizae, Trichoderma, Bacillus, Pseudomonas, other beneficial fungi.

Acts and rules (Specific to products)

Fertilizer (Control) Order, 1957/1985; Fertilizer (Movement Control) Order, 1960/1973; ECA Allocation Orders; FCO 2006/ 2009

Insecticides Act 1968; Insecticides Rules 1971; Pesticide Management Bill 2008

The Gazette of India Order dated 23rd February, 2021

Acts and rules (common to PGPR and other biologicals)

The Essential Commodities Act, 1955; The Biodiversity Act, 2002; The Seeds Act 1966; The Bureau of Indian Standards Act 2016

Nodal ministry/ Agency

Ministry of Agriculture

CIBRC under MOA

Role of Central Government

(i) Enactment and amendment of Acts and Rules from time to time; (ii) Registration of new chemical/ biofertilizers; (iii) Registration of industrial dealers; (iv) Ban/ restriction on use of registered products from time to time; (v) Allocation orders.

(i) Enactment and amendment of Acts and Rules from time to time; (ii) Registration of new chemical/ biopesticides; (iii) Ban/ restriction on use of registered products from time to time.

Role of State Governments

Enforcement: (i) Registration of manufacturers, importers and dealers; (ii) Production and distribution; (iii) Quality control (Fertilizer Inspector); (iv) Punitive actions for violation of provisions.

Enforcement: (i) Registration of manufacturers, importers, and dealers; (ii) Production and distribution; (iii) Quality control (Insecticide Inspector); (iv) Punitive actions for violation of provisions.

LEGISLATIONS ON BIOFERTILIZERS AND BIOPESTICIDES

The Biological Diversity Act, 2002

This Act regulates the accession and use of biological materials, development of biological based technologies/products and their patents, commercialization, equitable benefit sharing and licensing for commercial use in India and abroad by domestic and foreign organizations and nationals within India. The microorganism utilized for plant growth promoting microorganism manufacturing must be registered under this Act.

The Bureau of Indian Standards Act, 2016

This Act regulates the quality of goods and products through standard conformity and quality assurance. The Bureau of Indian Standards is the national standards body for standards formulation and certification marks.

COMMERCIALIZATION: IS IT A CHALLENGE IN THE FIELD OF BIOPESTICIDES?

The commercialization of biopesticides is a multistep process. Although it is easy for any research organization to identify any region-specific strain of biocontrol agents, it becomes quite difficult to bring them up to the level of commercial production. Because, any biocontrol agent has to undergo the same registration processes as any chemical pesticide, which is quite cumbersome, time-consuming and costly. Since there is no stability in the effect of biopesticides, farmers always had doubts. Again, due to the living nature of microbial biopesticides, several factors such as temperature, moisture, pH, ultraviolet spectrum, and soil factors can adversely affect their survival. Dealers and retailers are also least encouraged to promote biopesticides due to the short shelf-life of the products, low profit margins and lack of overall demand from farmers. All these together have resulted in limited adoption of biopesticides by farmers. However, in recent decades, the diffusion and use of natural and eco-friendly products for pests, diseases and nutrient management in agriculture has increased in India due to several reasons:

Climate change and sustainability

Climate change poses a threat to agriculture and livelihoods at the global level and India is one of the most affected countries owing to its huge population which is dependent on agriculture. Excessive and exploitative use of non-renewable resources such as petroleum products (for the production of chemical fertilizers and pesticides) is also a contributing factor to climate change.

Self-sufficiency in food production

India has attained self-sufficiency in grain production since the 1980s. This has enabled India to shift its focus to the quality of food production while sustaining the quantity of current level of food production. India’s current agricultural policies aim to achieve sustainable management of natural resources, sustainability of agriculture, enhancing farm incomes and eradicating malnutrition. Eco-friendly and green technologies are being promoted to gradually replace/ reduce chemical intensive agriculture.

Increasing awareness among consumers

Increasing quality of life and income levels has enabled urban population to be more aware of the quality of food products they consume. Healthy foods and lifestyles have become a priority, diverse, and chemical-free foods are sought after by this section of the society.

Increase in area under organic/ chemical-free agriculture

There is an increase in area under organic agriculture in India, which again illustrates the shift towards reduction in use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides as practiced in intensive agriculture. The total area dedicated to organic agriculture in Asia exceeded 5.9 million hectares in 2019. There were 1.4 million producers, most of them are in India. The leading countries by area were India (2.3 million ha) and China (over 2.2 million ha). With only 1.3% of total agricultural land under organic agriculture, India stands fifth among countries with the largest organic agricultural land area in 2019 at the global level (Hossain et al., 2021).

In India, a major technological breakthrough in biocontrol happened when chemical insecticides failed to control Helicoverpa armigera, Spodoptera litura, and other pests of cotton (Kranthi et al., 2002). It was realized that biocontrol is the safest, cost-effective, and eco-friendly method to control the widespread resistance of pests to chemical insecticides. Later, biopesticides became part of IPM which was previously completely based on the use of chemical pesticides (Misra et al., 2020) In this context, biopesticides play an important role in the promotion of eco-friendly and organic agriculture.

STATUS OF COMMERCIALIZATION, REJECTION AND ADOPTION OF BIOPESTICIDES BY THE FARMERS IN INDIA

In India, as of 2008, 15 biopesticides were registered under the Insecticides Act (1968), and their market share is only 4.2% of the overall pesticide market. However, it is predicted to increase at an annual growth rate of 10%. There are around 400 registered biopesticide active ingredients and over 1,250 actively registered biopesticide products in Indian markets (Anonymous, 2021). It shows the awareness among the farmers as well as policy support of the government to use the ecologically safe products for pest management. There are 970 biopesticide registrant companies in India by 2020 (Anonymous, 2021). However, the commercialization and adoption of the biopesticides in India is still low on account of several reasons:

TECHNICAL, LEGAL AND POLICY ISSUES ON NEW PRODUCT REGISTRATION

Even now, the guidelines for registration of biopesticide products draw too heavily on those for chemicals. In some cases, it is requested to supply information that is only relevant to chemical products and not biological products. A biocontrol preparation may sometimes aim at a small market. Being a live entity makes the biocontrol agent unique among control agents, which are usually chemical pesticides. A biocontrol agent is more affected by microclimate factors, and may need different attention regarding shipment, storage, and use. Potential users and distributors should be educated about its handling and need to be convinced about the value of a biocontrol product, which is somewhat more difficult to use than standard pesticides. Thus, adoption of these technologies by growers proceeds more slowly than expected. Indeed, in many places, farmers, agricultural advisors and even researchers and field personnel were not accustomed to the special handling and use demands that are imposed by the live biocontrol agent. Therefore, special instructions for biopesticide use had to be formulated and then had to be delivered along the chain of marketing, sales, and implementation.

During the more than last five decades, the area under bio-intensive IPM remained below 3% with biopesticides constituting only around 3% of pesticide market in the country. Present volume of around 27,000 tons of licensed production of registered biopesticides is a miniscule quantity for a large arable area of 142 million hectare in India. Nevertheless, biopesticides cannot qualify as alternatives to chemical pesticides, but can serve as an important component of disease management. Recently a gazette notification was released about the use of biocontrol agents where some of the genera of biocontrol agents were recently notified as biostimulants by GOI (Gazette Notification 2021). Therefore, chronic toxicology tests may not be required for these formulations, to enable easy and speedy registration of these bio-products.

FUTURE PROSPECTS

The establishment of a certification process to ensure the efficacy, quality, and consistency of biocontrol products would improve the global market perception of biopesticides as effective products. Data should be in the public domain and easily available to the farmers and extension workers. The effectiveness and safety of biocontrol products are essential for their successful commercialization. Farmers have to be educated that plant diseases have to be managed rather than completely controlled and that biologicals are an important part of the integrated pest management. Private companies are reluctant towards biocontrol R&D owing to limited market size, product inconsistency, and present methods of production, formulation and distribution. Recent advances in genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics can guide the development of next-generation bio-formulations with longer shelf-life.

REFERENCES

Anonymous (2021). Bio-pesticide registrant. Central insecticides Board and Registration committee,Directorate of Plant Protection, Quarantine and Storage, Department of Agriculture, Cooperation andFarmers Welfare, (CIB&RC) Government of India. http://ppqs.gov.in/divisions/cib-rc/biopesticideregistrant. Accessed 20Mar 2021

Arjjumend H, Koutouki K (2020) Legal Barriers and Quality Compliance in the Business of Biofertilizers and Biopesticides in India. J Legal Studies 26(40): 81-101.

Bhide R (2013) Regulatory perspective of agrochemicals in India, Agro News, July 19, 2013. Retrieved from http://news.agropages.com/News/NewsDetail-10045.htm

Kandpal V (2014) Biopesticides, Int J Environ Res Devl 4(2): 191-196.

Hossain ST, Chang J and Tagupta VJF (2021). Developments in organic sector in Asia in 2020 p198-2015. In Proceedings : The world of organic agriculture - statistics and emerging trends 2021, (Eds: Willer et al) Research Institute of Organic Agriculture FiBL, Frick, Switzerland and IFOAM Organics International, Bonn, p.340

Kranthi KR, Russell D, Wanjari R, Kherde M, Munje S, Lavhe N, Armes N (2002) In-season changes in resistance to insecticides in Helicoverpa armigera (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in India. J Econ Entomol 95(1): 134–142. https://doi.org/10.1603/0022-0493-95.1.134

Kumar V (2020) Union Budget 2020-21: Big talk on natural farming but no support. Down to Earth, 3 February 2020. Available at: https://www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/agriculture/union-budget-2020-21-big-talk-on-natural-farming-but-no-support-69131

Manjunatha BL, Hajong D, Tewari P, Singh Bhagwan, Shantaraja CS, Nikumbhe PH, Jat NK, Shiran K, Parihar RP (2018) Quality Seed Accessibility Index: A Case Study from a Village in Western Rajasthan. Indian J Ext Edu 54(1): 33-43.

Manjunatha B L, Rao DUM, Sharma JP, Burman RR, Hajong D, Dastagiri MB Sumanthkumar V (2015) Factors Affecting Accessibility, Use and Performance of Quality Seeds in Andhra Pradesh and Bihar: Farmers’ Experiences, J Community Mobil Sus Develp, 10(1): 130-145.

Mawar R, Manjunatha BL, Kumar S (2021) Commercialization, diffusion and adoption of bioformulations for sustainable disease management in Indian arid agriculture: Prospects and Challenges. Circular Eco Sustain p.19.https://doi.org/10.1007/s43615-021-00089-y

Mishra J, Dutta V, Arora NK (2020) Biopesticides in India: Technology and sustainable linkages. 3 Biotech 10(5): 210. doi: 10.1007/s13205-020-02192-7

MoA (2021a) Consumption of bio pesticides formulations in various states during 2016-17 to 2020-21, Directorate of Plant Protection, Quarantine and Storage, Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, GoI. Available at http://ppqs.gov.in/statistical-database. Accessed on 19/08/2021.

MoA (2021b) Bio-pesticide Registrant. Directorate of Plant Protection, Quarantine and Storage, Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, GoI. Available at http://ppqs.gov.in/divisions/cib-rc/bio-pesticide-registrant. Accessed on 19/08/2021.

Pathak DV, Singh S, Saini RS (2013) Impact of bio-inoculants on seed germination and plant growth of guava (Psidiumguajava). J Hort Forest 5(10):183-185.

Rakshit A, Meena VS, Parihar M, Singh HB, Singh AK (2021) Biofertilizers: Advances in Bio-inoculants. Volume 1. Elsevier p. 422.

Rakshit A, Meena VS, Abhilash PC, Sarma BK, Singh HB, Leonardo FracetoParihar M, Singh AK (2022) Biopesticides: Advances in Bioinoculants.Volume2 . Elsevier p.430.

Reddy MS, Rao DLN, Seshadri S, Krishna Sundari S, Sayyed,R.Z. (2021) Regulation of Plant Growth Promoting Microorganisms. Policy Paper No. 1., Asian PGPR Society, Auburn, Alabama, USA.

Sharma, K., Raju, S., Kumar, D. & Thakur, S. (2018). Biopesticides: an effective tool for insect pest management and current scenario in India, Indian Journal of Agriculture and Allied Sciences, 4(2), 59-62.

The Gazette of India. 2021. Order, Department of Agriculture, Cooperation and Farmers Welfare, Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, New Delhi, dated 23 February, 2021.

Singh, A., Jheeba, S. S.,Pramendra., Manjunatha, B. L. and Hajong, D. 2022. Adoption of chemical pesticides under commercial vegetable cultivation in Sri Ganganagardistrict of Rajasthan,Indian Journal of Extension Education, 58(1), 1-6.

Singh, H.B., Sarma, B.K. and Keswani, C. Eds. (2016). Agriculturally Important Microorganisms: Commercialization and Regulatory Requirements in Asia. Springer, Singapore p.305.

Singh, H.B and Anukool,Vaishnav. Eds. (2022). New and Future Developments in Microbial Biotechnology: Sustainable Agriculture: Microorganisms as Biostimulants. Elsevier p.374.

Singh, H.B and Anukool, Vaishnav. Eds.(2022). New and Future Developments in Microbial Biotechnology: Sustainable Agriculture:.Advances in microbe-based biostimulants. Elsevier p.457

Tarafdar, J.C. (2019) Fungalinoculants for native phosphorus mobilization. In: B. Giri et al. (eds.), Biofertilizers for Sustainable Agriculture and Environment, Soil Biology 55, Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-18933-4_