DOI: https://doi.org/10.56669/WEDK8256

ABSTRACT

The overreliance on chemical pesticides has led to the development of resistance, ecological disruption, and health issues, necessitating the pursuit of safer alternatives. Biopesticides, originating from natural organisms or their metabolites, offer precise pest management with diminished environmental consequences. They are categorized into microbial biopesticides, biochemical biopesticides, and plant-incorporated protectants (PIPs) created via genetic engineering. Notable successes include Bacillus thuringiensis in maize, Trichoderma spp. in horticultural crops, and nucleopolyhedroviruses in the management of lepidopteran pests. Innovations in nanoformulations and RNA interference (RNAi) technologies are addressing problems of insufficient stability, rapid degradation, and variable field efficacy. Biopesticides provide additional advantages such as compatibility with integrated pest management systems and enhancement of plant growth; however, their adoption is frequently constrained by regulatory obstacles, limited shelf life, and insufficient farmer awareness. Due to continuous advancements in biotechnology and formulation science, biopesticides are set to become essential components of sustainable, climate-resilient crop protection strategies.

Keywords: Biopesticides; Integrated Pest Management; RNAi; Nanotechnology; Sustainable Agriculture

INTRODUCTION

Chemical pesticides have been used extensively in modern agriculture in recent decades to sustain crop yields. Although these chemicals were effective initially, their prolonged use has led to major concerns about human health, environmental safety and the emergence of resistant pest populations (Ruiu, 2018). Farmers across the world are now facing declining efficacy of conventional pesticides alongside growing regulatory restrictions and consumer demand for residue-free produce (Isman, 2020).

Against this backdrop, biopesticides have emerged as a sustainable alternative. Derived from natural organisms or their metabolites, these products offer environmentally benign pest control with greater selectivity and reduced ecological disruption (Oliveira et al., 2021). Biopesticides typically decompose quickly, reduce collateral effects on non-target species, and can be incorporated into organic and integrated pest management (IPM) systems, in contrast to synthetic pesticides, which frequently have broad effects and persist in the environment (Gupta & Dikshit, 2010; Junaid et al., 2020). Therefore, the global push toward sustainable agriculture has therefore fueled renewed interest in developing novel biopesticide formulations and exploring new delivery platforms.

CLASSIFICATION OF BIOPESTICIDES

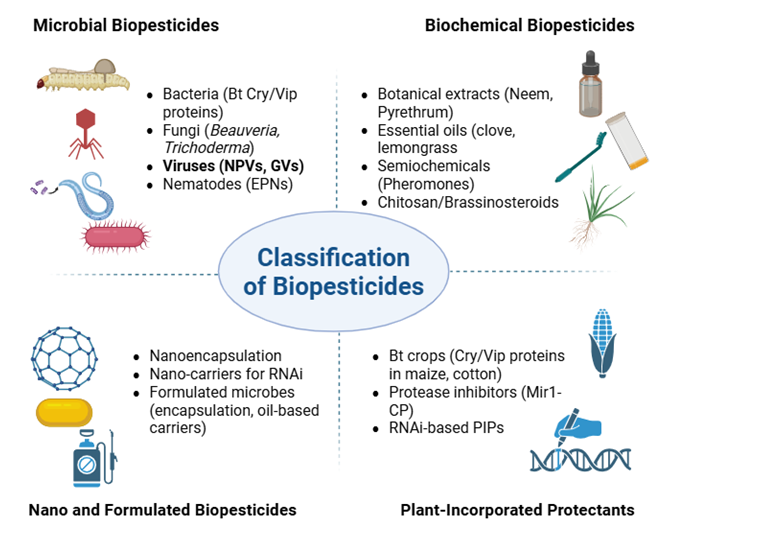

Biopesticides are generally grouped into three main categories: microbial, biochemical, and plant-incorporated protectants (PIPs). This three-layer classification, commonly utilized by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), has been reiterated subsequent reviews (Ruiu, 2018).

Microbial biopesticides are based on living organisms or their derivatives that specifically target pests. This encompasses bacteria like Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) and Pseudomonas fluorescens, fungi such as Trichoderma harzianum and Beauveria bassiana, insect-pathogenic viruses including nucleopolyhedroviruses, and entomopathogenic nematodes from the genera Steinernema and Heterorhabditis (Vero et al., 2023). Their specificity renders them effective means for lowering pest populations while preserving beneficial organisms.

Biochemical biopesticides, in contrast, rely on naturally occurring compounds or their analogues that influence pest behavior or physiology without direct toxicity. Notable examples include botanical extracts such as neem and pyrethrum, essential oils including clove and lemongrass, semiochemicals like pheromones utilized in mating disruption, and growth regulators such as chitosan (Tadesse et al., 2024). These compounds often act by hindering feeding, disrupting reproduction, or activating plant defense mechanisms.

Pesticidal substances known as plant-incorporated protectants (PIPs) are generated within plants as a result of genetic modification. Widely known examples include Bt-derived Cry and Vip proteins, protease inhibitors like Mir1-CP, and RNA interference (RNAi) constructs aimed at silencing critical pest genes (Tadesse et al., 2024). Embedding pesticidal traits within the plant itself allows for season-long protection and minimizes the necessity for repeated pesticide applications.

.png)

Fig. 1. Classification of Biopesticides into microbial, biochemical, nano/formulated biopesticides, and plant-incorporated protectants based on their origin and application

Data source: Compiled by the author based on Chandler et al., 2011

In addition to the EPA framework, various international organizations, including the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) / World Health Organization (WHO), and International Biocontrol Manufacturers Association (IBMA), have put forth supplementary categories. This includes invertebrate biocontrol agents, such as predators and parasitoids, as well as agricultural antibiotics and botanicals, reflecting the diversity of natural products being harnessed for pest management (Ruiu, 2018). Classification schemes also show geographical variation. For instance, while the European Union regulates biopesticides under its general “plant protection products” framework, China identifies five distinct categories- microbial, biochemical, botanical, agricultural antibiotics, and natural enemies- offering a broader regulatory perspective (Tadesse et al., 2024).

More recently, proposals have been made to incorporate novel classes, such as RNAi-based products and nano-enabled formulations. The newly identified categories demonstrate advancements in technology designed to address certain drawbacks of conventional biopesticides, especially regarding stability, delivery, and resistance management (Vero et al., 2023).

Microbial biopesticides

Microbial biopesticides represent one of the most extensively studied and commercially successful categories. They are formulated from living microorganisms—bacteria, fungi, viruses, or nematodes—or from their active metabolites and are widely recognized for their high specificity toward target pests. They are essential components of integrated pest management strategies due to their diverse mechanisms of action and adoption for sustainable practices (Ruiu, 2018; Vero et al., 2023).

Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) has remained the most widely recognized example of bacteria. The midgut epithelium of insect larvae is disrupted by the crystalline (Cry) and vegetative insecticidal (Vip) proteins produced by Bt, which cause paralysis and death. Bt has been effectively used against a variety of lepidopteran, coleopteran, and dipteran pests since its initial field application in the middle of the 20th century (Bravo et al., 2017; Chakraborty et al., 2022). By promoting plant systemic resistance and producing antagonistic metabolites, other bacterial agents like Pseudomonas fluorescens and Streptomyces species have shown promise in controlling soil-borne pathogens, both through antagonistic metabolites and by stimulating plant systemic resistance (Gupta & Dikshit, 2010; Oliveira et al., 2021).

Fungal biopesticides have also gained significant attention. Trichoderma harzianum, for instance, functions not only as a mycoparasite but also enhances plant growth by inducing systemic resistance. Likewise, entomopathogenic fungi like Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae infect insects by penetrating their cuticles directly. They then multiply inside the host hemocoel and produce deadly toxins (Mascarin & Jaronski, 2016; Jaber & Ownley, 2018). Commercial formulations of these fungi are now widely accessible, and they have shown effectiveness against a variety of insect pests, such as termites, aphids, and whiteflies.

Viruses, particularly nucleopolyhedroviruses (NPVs) and granuloviruses (GVs), offer another layer of microbial pest control. To ensure effective horizontal transmission, these occlusion body-forming viruses first infect insect larvae, then multiply systemically and finally liquefy the host. Particularly valued for their host specificity and low non-target effects, viral biopesticides are appropriate for ecological farming systems (Haase et al., 2015; Erlandson, 2020). Another class of microbial biocontrol agents are entomopathogenic nematodes (EPNs), particularly those belonging to the genera Steinernema and Heterorhabditis. Following nematode penetration, symbiotic bacteria (Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus spp.) are released into the insect hemocoel via these nematodes. While offering a nutrient-rich environment for nematode reproduction, the bacteria quickly kill the host (Kaya et al., 2006; Shapiro-Ilan et al., 2017). Due to their adaptability, they have been effectively used to combat soil-dwelling pests like cutworms, weevils, and grubs.

Despite their potential, microbial biopesticides have a few challenges. Their performance in the field can be inconsistent, as environmental conditions such as UV radiation, rainfall, and temperature fluctuations often reduce efficacy (Chandler et al., 2011). However, these limitations are being addressed, and product shelf life is being increased by advancements in formulation technology, including encapsulation, oil-based carriers, and nanoparticle delivery systems (Kalia et al., 2023). As a result, microbial biopesticides continue to expand their footprint in both conventional and organic agriculture, offering safer, eco-friendly solutions to pest control.

Biochemical biopesticides

Biochemical biopesticides are a broad category of naturally occurring substances or their synthetic counterparts that affect the growth, behavior, or reproduction rather than causing direct toxicity. They are frequently regarded as important tools in sustainable agriculture due to their ecological safety and specificity and are increasingly incorporated into integrated pest management programs (Isman, 2020; Tadesse et al., 2024).

One of the most widely studied categories within this group is botanical extracts. Azadirachtin, for instance, is found in neem (Azadirachta indica), which acts as a feeding deterrent and disrupts insect molting and reproduction. Similarly, because of its neurotoxic effects on insect nervous systems, pyrethrum, which is derived from Chrysanthemum cinerariifolium, has been used as a natural insecticide for decades (Isman, 2020). Although they are used less frequently now due to safety concerns, other plant-derived compounds like rotenone demonstrate the long-standing use of botanicals in pest control (Pavela & Benelli, 2016).

Essential oils have also emerged as effective biopesticides. Oils extracted from clove, lemongrass, and eucalyptus have shown strong repellent, insecticidal, and antifungal activities. They are less likely to develop resistance owing to their various modes of action, which include membrane disruption, respiratory inhibition, and interference with neurotransmission (Regnault-Roger et al., 2012; Benelli et al., 2018). Furthermore, essential oils often leave minimal residues, making them suitable for organic farming systems.

Natural growth regulators like chitosan and brassinosteroids are gaining attention for their dual functions in promoting plant health and managing pests. Derived from chitin, chitosan can enhance crop resistance to abiotic stresses, inhibit fungal growth, and initiate plant defense responses (El Hadrami et al., 2010; Malerba & Cerana, 2016). Brassinosteroids, while primarily known as plant hormones, also enhance resistance against insect and pathogen attack through activation of systemic defense pathways (Nakashita et al., 2003).

The increasing array of biochemical biopesticides demonstrates their versatility in combating various pest pressures and promoting environmentally conscious crop production. However, variability in the concentration of active compounds, quick degradation in the field, and comparatively high production costs are still major obstacles (Pavela & Benelli, 2016). The stability and persistence of these compounds are being enhanced by emerging formulation techniques, such as encapsulation and nanoemulsion technologies, indicating that biochemical biopesticides will become increasingly significant in future crop protection systems.

Plant-incorporated protectants (PIPs)

Plant-incorporated protectants (PIPs) represent a distinct category of biopesticides in which plants are genetically engineered to produce pesticidal substances within their own tissues. PIPs offer continuous protection throughout the plant's lifecycle, eliminating the need for repeated pesticide applications and providing continuous protection throughout the plant’s lifecycle, in contrast to microbial or biochemical products that typically require external application (Ruiu, 2018; Tadesse et al., 2024).

The most widely adopted PIPs are those expressing Bt-derived proteins, particularly Cry and Vip toxins. These proteins specifically target insect pests by binding to receptors in the midgut, causing pore formation, cell lysis, and ultimately insect death. Nowadays, Bt cotton and Bt maize are grown extensively across several continents, contributing to integrated pest management strategies and significantly lowering the use of chemical insecticides (James, 2018; Chakraborty et al., 2022).

Other protein-based defenses have been incorporated into plants in addition to Bt. For instance, maize lines expressing the cysteine protease inhibitor Mir1-CP have shown resistance to fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) by disrupting insect digestive processes (Pechan et al., 2000). Such innovations demonstrate the potential of PIPs to expand pest resistance mechanisms beyond the classic Bt framework.

A more recent frontier is RNA interference (RNAi)-based PIPs, in which plants are engineered to produce double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) that silences essential pest genes. Targeting lepidopteran and coleopteran pests with this strategy has shown promising results; studies have shown that when insects eat plants that express dsRNA, their survival and feeding rates are significantly reduced (Joga et al., 2016; Mat Jalaluddin et al., 2019). New approaches to broad-spectrum biocontrol are being explored by testing RNAi-based tactics against plant-parasitic nematodes.

In addition, secondary metabolites derived from bacteria and fungi have been expressed in plants to broaden resistance profiles. For example, crop plants have been modified to produce genes encoding toxins from the bacteria Photorhabdus and Xenorhabdus, which may improve resistance to a variety of insect pests (Stock et al., 2017).

Despite these successes, the use of PIPs is not without controversy. Public acceptance, probable non-target impacts, and the emergence of pest resistance continue to be major obstacles to widespread adoption (Tabashnik & Carrière, 2017). To address these issues, commercial crops are utilizing resistance management techniques, such as pyramiding multiple genes and refuge planting. (Carrière et al., 2016). Furthermore, advances in gene-editing technologies, such as CRISPR/Cas, are expected to provide more precise and durable options for engineering PIPs in the future (Kanchiswamy, 2016).

Taken together, PIPs show how genetic engineering can offer reliable, focused, and long-lasting pest control solutions. While challenges remain, ongoing research and regulatory refinement suggest that PIPs will continue to play an important role in next-generation crop protection.

Nano- and formulated biopesticides

A significant limitation of many biopesticides is their short shelf life and inconsistent performance under field conditions. While rapid degradation can limit residual activity, environmental factors such as UV radiation, rainfall, and high temperatures often reduce efficacy. Recent studies have focused on advanced formulations and delivery systems based on nanotechnology to overcome these limitations and enhance the stability, accuracy, and efficacy of biopesticides (Kalia et al., 2023; Kumar et al., 2022).

Nanoformulations represent one of the most promising approaches. Biopesticides, such as plant extracts, microbial metabolites, or double-stranded RNA, can be encapsulated in nanocarriers to increase solubility, shield active ingredients from deterioration, and guarantee controlled release. For example, chitosan nanoparticles loaded with dsRNA have been shown to protect RNA molecules from enzymatic breakdown in insect guts, thereby enhancing RNA interference efficiency against pests such as Helicoverpa armigera (Kumar et al., 2022). The delivery of dsRNA targeting important developmental genes in Grapholita molesta has also been made feasible by polymer-based nanocarriers, which has a major negative impact on larval growth and reproduction (Quílez-Molina et al., 2024).

Nano-encapsulated botanical extracts and essential oils are becoming more popular in addition to RNAi applications. In comparison to traditional sprays, plant-derived oils such as neem and clove, when prepared as nanoemulsions, show better stability, increased penetration into insect cuticles, and prolonged activity (Ghormade et al., 2011; Benelli, 2018). Additionally, these nanoemulsions minimize environmental residues and application costs by enabling lower dosages without compromising efficacy.

Furthermore, formulation technology is essential in expanding the reach of microbial biopesticides. To increase the shelf life of bacterial and fungal products and make them easier to use in the field, encapsulated beads, wettable powders, and oil-based suspensions have been developed (Mascarin & Jaronski, 2016). Recent advances in UV protectants and carrier materials are further helping to stabilize sensitive organisms such as baculoviruses, making them more reliable under fluctuating environmental conditions (Haase et al., 2015).

The commercial use of nanopesticides and biopesticide formulations is still in the stages of development. Questions remain about large-scale production costs, regulatory approval, and potential risks of nanoparticle accumulation in the environment (Kalia et al., 2023). Nonetheless, the rapid progress in this area suggests that smart formulations will play an increasingly important role in overcoming the inherent limitations of traditional biopesticides, ultimately improving their consistency and effectiveness in real-world farming systems.

MODE OF ACTION OF BIOPESTICIDES

The effectiveness of biopesticides lies in their diverse and often highly specific mechanisms of action, which distinguish them from conventional synthetic pesticides. Rather than causing broad-spectrum toxicity, biopesticides typically target physiological processes in pests, making them safer for non-target organisms and the environment (Ruiu, 2018; Chandler et al., 2011).

The Cry and Vip proteins, for instance, are produced by bacterial agents like Bacillus thuringiensis and bind to receptors in the midgut of insects, resulting in pore formation, osmotic balance disruption, and ultimately larval death (Bravo et al., 2017; Chakraborty et al., 2022). Fungal pathogens like Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae exhibit a similar level of precision. They use degradative enzymes to penetrate through the insect's cuticle and multiply within the hemocoel, releasing toxins that quickly kill the host (Mascarin & Jaronski, 2016; Jaber & Ownley, 2018).

Viruses offer an additional strategy. Nucleopolyhedroviruses replicate inside insect cells, which results in systemic infections, larval disintegration, and the subsequent dissemination of viral particles throughout the environment (Haase et al., 2015; Erlandson, 2020). Entomopathogenic nematodes adopt a different but equally efficient approach, vectoring symbiotic bacteria such as Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus, which quickly establish lethal septicemia inside the host insect (Shapiro-Ilan et al., 2017).

Table 1. Table summarizing key biopesticides, their target pests or diseases, and modes of action in major crops.

|

Crop

|

Biocontrol Agent

|

Type

|

Target Pest/Disease

|

Mode of Action / Impact

|

Reference

|

|

Cotton, Maize, Rice, Vegetables

|

Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) Cry & Vip proteins

|

Microbial (Bacterium) / PIP

|

Lepidopteran, coleopteran, dipteran insects

|

Midgut binding → pore formation → larval death; incorporated in Bt cotton/maize → reduced insecticide use

|

(Bravo et al., 2017; Chakraborty et al., 2022)

|

|

Rice, Wheat, Tomato

|

Pseudomonas fluorescens

|

Microbial (Bacterium)

|

Soil-borne pathogens (Fusarium, Rhizoctonia, Pythium)

|

Antagonistic metabolites; induces systemic resistance

|

(Gupta & Dikshit, 2010; Oliveira et al., 2021)

|

|

Maize, Sorghum, Vegetables

|

Trichoderma harzianum

|

Microbial (Fungus)

|

Soil-borne fungal pathogens

|

Mycoparasitism, antibiotic production, ISR; also promotes growth

|

(Mascarin & Jaronski, 2016; Jaber & Ownley, 2018)

|

|

Vegetables, Fruits, Cereals

|

Beauveria bassiana, Metarhizium anisopliae

|

Microbial (Fungi)

|

Aphids, whiteflies, termites, beetles

|

Cuticle penetration → proliferation in hemocoel → insect death

|

(Mascarin & Jaronski, 2016; Jaber & Ownley, 2018)

|

|

Sugarcane, Cotton, Maize

|

Nucleopolyhedroviruses (NPVs), Granuloviruses (GVs)

|

Microbial (Viruses)

|

Lepidopteran larvae

|

Ingestion → systemic infection → larval liquefaction → horizontal spread

|

(Haase et al., 2015; Erlandson, 2020)

|

|

Vegetables, Ornamentals, Turf

|

Steinernema spp., Heterorhabditis spp. (with Xenorhabdus/Photorhabdus bacteria)

|

Microbial (Nematodes)

|

Soil-dwelling pests (cutworms, grubs, weevils)

|

Nematode invasion → bacterial release → septicemia → insect death

|

(Kaya et al., 2006; Shapiro-Ilan et al., 2017)

|

|

Cotton, Rice, Pulses

|

Neem (Azadirachtin)

|

Biochemical (Botanical)

|

Lepidopterans, sap-feeding insects

|

Feeding deterrent, molting disruption, reproductive inhibition

|

(Isman, 2020; Pavela & Benelli, 2016)

|

|

Vegetables, Fruits, Cereals

|

Pyrethrum (Chrysanthemum extract)

|

Biochemical (Botanical)

|

Aphids, thrips, beetles

|

Neurotoxic to insect nervous system

|

(Isman, 2020)

|

|

Various crops

|

Essential oils (clove, lemongrass, eucalyptus)

|

Biochemical

|

Insects, fungi

|

Repellence, membrane disruption, neurotoxicity

|

(Regnault-Roger et al., 2012; Benelli et al., 2018)

|

|

Maize

|

Mir1-CP (protease inhibitor expressed in transgenic maize)

|

PIP

|

Fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda)

|

Disrupts insect digestion → resistance

|

(Pechan et al., 2000)

|

|

Maize, Potato, Soybean

|

RNAi-based PIPs

|

PIP

|

Lepidopteran & coleopteran pests

|

dsRNA → gene silencing → impaired development & survival

|

(Joga et al., 2016; Mat Jalaluddin et al., 2019)

|

Other biopesticides function more by disrupting the behavior or development of pests rather than killing them. Compounds like azadirachtin from neem disrupt insect molting and reproduction while also deterring feeding, whereas essential oils such as clove and eucalyptus destabilize cell membranes and impair neurological function, producing strong repellent or toxic effects (Isman, 2020; Benelli et al., 2018). Instead of directly killing pests, semiochemicals such as sex pheromones used in mating disruption lower populations by preventing reproductive success (Witzgall et al., 2010).

Recent innovations increasingly rely on genetic engineering. Crops that express pesticidal proteins or double-stranded RNA molecules affect critical pest genes upon consumption, resulting in developmental arrest or mortality. This approach broadens the application of biopesticides from external application to integration within the plant system itself (Joga et al., 2016; Mat Jalaluddin et al., 2019).

These different mechanisms highlight the efficacy of biopesticides, as they utilize multiple modes of toxicity to target a spectrum of molecular, physiological, and behavioral weaknesses in pests. This diversity reduces unintended ecological consequences and provides opportunities to combine various products, enhancing efficacy and mitigating resistance development.

ADVANTAGES AND LIMITATIONS

The environmental safety of biopesticides represents a significant advantage. Due to their origin from natural organisms or compounds, these substances tend to decompose quickly and result in minimal residues in soil, water, or food products. This characteristic enhances their compatibility with organic farming systems and aligns with consumer preferences for residue-free produce (Gupta & Dikshit, 2010; Oliveira et al., 2021). Their high specificity is a notable strength, as most biopesticides target specific pests while leaving beneficial insects, pollinators, and natural enemies unharmed, thus promoting ecological balance and biodiversity in agroecosystems (Chandler et al., 2011; Jaber & Ownley, 2018). The diverse modes of action, including midgut disruption in insects and behavioral modification via pheromones, decrease the probability of rapid resistance development relative to synthetic pesticides, particularly when incorporated into integrated pest management programs (Bravo et al., 2017; Witzgall et al., 2010).

Also, biopesticides provide benefits that extend beyond mere pest control. Specific microbial agents, including Trichoderma spp. and Pseudomonas fluorescens, exhibit dual functions by controlling pathogens and promoting plant growth, as well as inducing systemic resistance, which enhances crop vigor and yield stability (El Hadrami et al., 2010; Junaid et al., 2020). Essential oils and chitosan, meanwhile, combine antimicrobial or insecticidal activity with the ability to enhance plant defense pathways, further highlighting their multifunctional benefits (Malerba & Cerana, 2016; Benelli et al., 2018).

Despite these strengths, the use of biopesticides is constrained by several limitations. Their efficacy is often less predictable than that of synthetic pesticides, vastly because environmental factors such as UV radiation, rainfall, and temperature fluctuations can reduce their persistence and effectiveness in the field (Chandler et al., 2011; Mascarin & Jaronski, 2016). The scalability of microbial products is further restricted by their short shelf life and the requirement for specific storage conditions, especially in areas with inadequate infrastructure (Shapiro-Ilan et al., 2017). Variability in active compound concentration is also a challenge for botanical extracts and essential oils, as factors like plant source, harvest time, and processing methods can significantly affect product consistency (Pavela & Benelli, 2016; Isman, 2020).

Economic and regulatory barriers add another layer of difficulty. Commercialization may be delayed by navigating complicated and occasionally contradictory regulatory frameworks, and biopesticide development frequently entails high research and production costs (Oliveira et al., 2021). Due to a lack of knowledge, inadequate training, or the belief that biopesticides are less effective than traditional chemicals, farmers may be reluctant to use them, especially in developing nations (Kalia et al., 2023).

Taken together, these benefits and drawbacks highlight the potential and difficulties of biopesticides in contemporary agriculture. Although their sustainability credentials and ecological advantages are indisputable, their full potential will depend on resolving adoption, cost, and stability concerns.

FUTURE PROSPECTS OF BIOPESTICIDES

Looking ahead, the future of biopesticides is closely tied to advances in biotechnology, formulation science, and integrated pest management strategies. One of the most promising fields is RNA interference (RNAi), which offers previously unprecedented precision in targeting vital genes of insects, nematodes, and even plant pathogens. RNAi may be able to resolve stability problems and make field-ready applications possible when paired with delivery systems based on nanotechnology (Joga et al., 2016; Kumar et al., 2022). The shelf life and field performance of microbial agents and botanical extracts are also anticipated to be significantly enhanced by advancements in encapsulation and controlled-release formulations, which will lower one of the primary adoption barriers (Ghormade et al., 2011; Kalia et al., 2023).

Another area of growth lies in the integration of biopesticides with digital agriculture and precision farming tools. More focused biopesticide applications could be explored with developments in remote sensing, pest forecasting, and decision-support systems, which would minimize waste and increase effectiveness (Chakraborty et al., 2022; Oliveira et al., 2021). At the same time, genome editing tools like CRISPR/Cas could help create new plant-based defenses and modified microorganisms that are more resilient and effective (Kanchiswamy, 2016; Tabashnik & Carrière, 2017).

Efforts to tackle socio-economic and regulatory issues will be equally essential. The widespread use of biopesticides will require incentives for adoption, standardized approval procedures, and expanded farmer training, especially in areas where chemical pesticides continue to dominate pest management (Oliveira et al., 2021; Tadesse et al., 2024). Biopesticides are positioned to play a bigger role in agriculture as it moves toward more climate-resilient and sustainable systems—not as alternatives to traditional methods, but as essential supplements.

REFERENCES

Benelli, G., Pavela, R., Canale, A., & Mehlhorn, H. (2018). Tick repellents and acaricides of botanical origin: A green roadmap to control tick-borne diseases? Parasitology Research, 117, 45–60.

Bravo, A., Likitvivatanavong, S., Gill, S. S., & Soberón, M. (2017). Bacillus thuringiensis: A story of a successful bioinsecticide. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 41, 423–431.

Carrière, Y., Crickmore, N., & Tabashnik, B. E. (2016). Optimizing pyramided transgenic Bt crops for sustainable pest management. Nature Biotechnology, 33, 161–168.

Chandler, D., Bailey, A. S., Tatchell, G. M., Davidson, G., Greaves, J., & Grant, W. P. (2011). The development, regulation and use of biopesticides for integrated pest management. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 366, 1987–1998.

Chakraborty, S., Newton, A. C., & Allard, R. W. (2022). Harnessing microbial biopesticides for sustainable agriculture. Frontiers in Agronomy, 4, 22–34.

El Hadrami, A., Adam, L. R., El Hadrami, I., & Daayf, F. (2010). Chitosan in plant protection. Marine Drugs, 8, 968–987.

Erlandson, M. (2020). Insect pest control by viruses. Canadian Entomologist, 152, 481–490.

Ghormade, V., Deshpande, M. V., & Paknikar, K. M. (2011). Perspectives for nano-biotechnology enabled protection and nutrition of plants. Biotechnology Advances, 29, 792–803.

Gupta, S., & Dikshit, A. K. (2010). Biopesticides: An eco-friendly approach for pest control. Journal of Biopesticides, 3, 186–188.

Haase, S., Sciocco-Cap, A., Romanowski, V., & Ferrelli, M. L. (2015). Baculovirus insecticides in Latin America: Historical overview, current status and future perspectives. Viruses, 7, 2230–2267.

Isman, M. B. (2020). Botanical insecticides in the twenty-first century: New horizons and old barriers. Annual Review of Entomology, 65, 233–249.

Jaber, L. R., & Ownley, B. H. (2018). Can we use entomopathogenic fungi as endophytes for dual biological control of insect pests and plant pathogens? Biological Control, 116, 36–45.

James, C. (2018). Global status of commercialized biotech/GM crops: 2018. ISAAA Briefs, 54, 1–123.

Joga, M. R., Zotti, M. J., Smagghe, G., & Christiaens, O. (2016). RNAi efficiency, systemic properties, and novel delivery methods for pest insect control: What we know so far. Frontiers in Physiology, 7, 553.

Junaid, J. M., Dar, N. A., Bhat, T. A., Bhat, A. H., & Bhat, M. A. (2020). Commercial biopesticides in plant disease management. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology, 23, 101485.

Kalia, A., Abd-Elsalam, K. A., & Kuca, K. (2023). Nano-biopesticides today and future perspectives. Frontiers in Plant Science, 14, 111–126.

Kanchiswamy, C. N. (2016). DNA-free genome editing methods for targeted crop improvement. Plant Cell Reports, 35, 1469–1474.

Kaya, H. K., & Gaugler, R. (2006). Entomopathogenic nematodes: Utility in IPM. Annual Review of Entomology, 38, 181–206.

Kumar, P., Pandey, P., Sharma, R., & Thakur, R. (2022). Nanotechnology interventions in sustainable agriculture: Recent advances and future prospects. Frontiers in Nanotechnology, 4, 855–868.

Malerba, M., & Cerana, R. (2016). Chitosan effects on plant systems. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 17, 996.

Mascarin, G. M., & Jaronski, S. T. (2016). The production and uses of Beauveria bassiana as a microbial insecticide. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 32, 177.

Mat Jalaluddin, N. S., Finka, A., & Golombek, A. J. (2019). RNAi in crop protection: Strategies and challenges. Plants, 8, 496.

Oliveira, B. M., Lima, F. V., & Moreira, J. M. (2021). Biopesticides: A promising alternative for sustainable agriculture. Journal of Cleaner Production, 316, 128147.

Pavela, R., & Benelli, G. (2016). Essential oils as ecofriendly biopesticides? Challenges and constraints. Trends in Plant Science, 21, 1000–1016.

Pechan, T., Ye, L., Chang, Y. M., Mitra, A., Lin, L., Davis, F. M., Williams, W. P., & Luthe, D. S. (2000). A unique 33-kD cysteine proteinase accumulates in response to larval feeding in maize genotypes resistant to fall armyworm. Plant Cell, 12, 1031–1040.

Quílez-Molina, A. I., González-González, E., Martínez-Guitián, M., & Vázquez, C. (2024). Nanocarrier-mediated delivery of dsRNA for sustainable pest management. Pest Management Science, 80, 1456–1470.

Regnault-Roger, C., Vincent, C., & Arnason, J. T. (2012). Essential oils in insect control: Low-risk products in a high-stakes world. Annual Review of Entomology, 57, 405–424.

Ruiu, L. (2018). Microbial biopesticides in agroecosystems. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 102, 2949–2954.

Shapiro-Ilan, D. I., Han, R., & Dolinski, C. (2017). Entomopathogenic nematode production and application technology. Journal of Nematology, 49, 1–17.

Stock, S. P., Rivera-Orduna, F. N., Flores-Lara, Y., & Flores-Lara, J. (2017). Heterorhabditis bacteriophora and its bacterial symbionts as potential sources of novel natural products. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 150, 1–12.

Tabashnik, B. E., & Carrière, Y. (2017). Surge in insect resistance to transgenic crops and prospects for sustainability. Nature Biotechnology, 35, 926–935.

Tadesse, T. M., Alemu, T., & Tesfaye, A. (2024). Biopesticides in sustainable agriculture: Trends and innovations. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 8, 155.

Vero, A., Giorgi, V., & Scariot, V. (2023). Microbial biopesticides in agroecosystems: Recent advances and perspectives. Microorganisms, 11, 203.

Witzgall, P., Kirsch, P., & Cork, A. (2010). Sex pheromones and their impact on pest management. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 36, 80–100.

Revolutionizing Crop Protection - Emerging Biopesticide Technologies and their Future Potential

DOI: https://doi.org/10.56669/WEDK8256

ABSTRACT

The overreliance on chemical pesticides has led to the development of resistance, ecological disruption, and health issues, necessitating the pursuit of safer alternatives. Biopesticides, originating from natural organisms or their metabolites, offer precise pest management with diminished environmental consequences. They are categorized into microbial biopesticides, biochemical biopesticides, and plant-incorporated protectants (PIPs) created via genetic engineering. Notable successes include Bacillus thuringiensis in maize, Trichoderma spp. in horticultural crops, and nucleopolyhedroviruses in the management of lepidopteran pests. Innovations in nanoformulations and RNA interference (RNAi) technologies are addressing problems of insufficient stability, rapid degradation, and variable field efficacy. Biopesticides provide additional advantages such as compatibility with integrated pest management systems and enhancement of plant growth; however, their adoption is frequently constrained by regulatory obstacles, limited shelf life, and insufficient farmer awareness. Due to continuous advancements in biotechnology and formulation science, biopesticides are set to become essential components of sustainable, climate-resilient crop protection strategies.

Keywords: Biopesticides; Integrated Pest Management; RNAi; Nanotechnology; Sustainable Agriculture

INTRODUCTION

Chemical pesticides have been used extensively in modern agriculture in recent decades to sustain crop yields. Although these chemicals were effective initially, their prolonged use has led to major concerns about human health, environmental safety and the emergence of resistant pest populations (Ruiu, 2018). Farmers across the world are now facing declining efficacy of conventional pesticides alongside growing regulatory restrictions and consumer demand for residue-free produce (Isman, 2020).

Against this backdrop, biopesticides have emerged as a sustainable alternative. Derived from natural organisms or their metabolites, these products offer environmentally benign pest control with greater selectivity and reduced ecological disruption (Oliveira et al., 2021). Biopesticides typically decompose quickly, reduce collateral effects on non-target species, and can be incorporated into organic and integrated pest management (IPM) systems, in contrast to synthetic pesticides, which frequently have broad effects and persist in the environment (Gupta & Dikshit, 2010; Junaid et al., 2020). Therefore, the global push toward sustainable agriculture has therefore fueled renewed interest in developing novel biopesticide formulations and exploring new delivery platforms.

CLASSIFICATION OF BIOPESTICIDES

Biopesticides are generally grouped into three main categories: microbial, biochemical, and plant-incorporated protectants (PIPs). This three-layer classification, commonly utilized by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), has been reiterated subsequent reviews (Ruiu, 2018).

Microbial biopesticides are based on living organisms or their derivatives that specifically target pests. This encompasses bacteria like Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) and Pseudomonas fluorescens, fungi such as Trichoderma harzianum and Beauveria bassiana, insect-pathogenic viruses including nucleopolyhedroviruses, and entomopathogenic nematodes from the genera Steinernema and Heterorhabditis (Vero et al., 2023). Their specificity renders them effective means for lowering pest populations while preserving beneficial organisms.

Biochemical biopesticides, in contrast, rely on naturally occurring compounds or their analogues that influence pest behavior or physiology without direct toxicity. Notable examples include botanical extracts such as neem and pyrethrum, essential oils including clove and lemongrass, semiochemicals like pheromones utilized in mating disruption, and growth regulators such as chitosan (Tadesse et al., 2024). These compounds often act by hindering feeding, disrupting reproduction, or activating plant defense mechanisms.

Pesticidal substances known as plant-incorporated protectants (PIPs) are generated within plants as a result of genetic modification. Widely known examples include Bt-derived Cry and Vip proteins, protease inhibitors like Mir1-CP, and RNA interference (RNAi) constructs aimed at silencing critical pest genes (Tadesse et al., 2024). Embedding pesticidal traits within the plant itself allows for season-long protection and minimizes the necessity for repeated pesticide applications.

Fig. 1. Classification of Biopesticides into microbial, biochemical, nano/formulated biopesticides, and plant-incorporated protectants based on their origin and application

Data source: Compiled by the author based on Chandler et al., 2011

In addition to the EPA framework, various international organizations, including the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) / World Health Organization (WHO), and International Biocontrol Manufacturers Association (IBMA), have put forth supplementary categories. This includes invertebrate biocontrol agents, such as predators and parasitoids, as well as agricultural antibiotics and botanicals, reflecting the diversity of natural products being harnessed for pest management (Ruiu, 2018). Classification schemes also show geographical variation. For instance, while the European Union regulates biopesticides under its general “plant protection products” framework, China identifies five distinct categories- microbial, biochemical, botanical, agricultural antibiotics, and natural enemies- offering a broader regulatory perspective (Tadesse et al., 2024).

More recently, proposals have been made to incorporate novel classes, such as RNAi-based products and nano-enabled formulations. The newly identified categories demonstrate advancements in technology designed to address certain drawbacks of conventional biopesticides, especially regarding stability, delivery, and resistance management (Vero et al., 2023).

Microbial biopesticides

Microbial biopesticides represent one of the most extensively studied and commercially successful categories. They are formulated from living microorganisms—bacteria, fungi, viruses, or nematodes—or from their active metabolites and are widely recognized for their high specificity toward target pests. They are essential components of integrated pest management strategies due to their diverse mechanisms of action and adoption for sustainable practices (Ruiu, 2018; Vero et al., 2023).

Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) has remained the most widely recognized example of bacteria. The midgut epithelium of insect larvae is disrupted by the crystalline (Cry) and vegetative insecticidal (Vip) proteins produced by Bt, which cause paralysis and death. Bt has been effectively used against a variety of lepidopteran, coleopteran, and dipteran pests since its initial field application in the middle of the 20th century (Bravo et al., 2017; Chakraborty et al., 2022). By promoting plant systemic resistance and producing antagonistic metabolites, other bacterial agents like Pseudomonas fluorescens and Streptomyces species have shown promise in controlling soil-borne pathogens, both through antagonistic metabolites and by stimulating plant systemic resistance (Gupta & Dikshit, 2010; Oliveira et al., 2021).

Fungal biopesticides have also gained significant attention. Trichoderma harzianum, for instance, functions not only as a mycoparasite but also enhances plant growth by inducing systemic resistance. Likewise, entomopathogenic fungi like Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae infect insects by penetrating their cuticles directly. They then multiply inside the host hemocoel and produce deadly toxins (Mascarin & Jaronski, 2016; Jaber & Ownley, 2018). Commercial formulations of these fungi are now widely accessible, and they have shown effectiveness against a variety of insect pests, such as termites, aphids, and whiteflies.

Viruses, particularly nucleopolyhedroviruses (NPVs) and granuloviruses (GVs), offer another layer of microbial pest control. To ensure effective horizontal transmission, these occlusion body-forming viruses first infect insect larvae, then multiply systemically and finally liquefy the host. Particularly valued for their host specificity and low non-target effects, viral biopesticides are appropriate for ecological farming systems (Haase et al., 2015; Erlandson, 2020). Another class of microbial biocontrol agents are entomopathogenic nematodes (EPNs), particularly those belonging to the genera Steinernema and Heterorhabditis. Following nematode penetration, symbiotic bacteria (Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus spp.) are released into the insect hemocoel via these nematodes. While offering a nutrient-rich environment for nematode reproduction, the bacteria quickly kill the host (Kaya et al., 2006; Shapiro-Ilan et al., 2017). Due to their adaptability, they have been effectively used to combat soil-dwelling pests like cutworms, weevils, and grubs.

Despite their potential, microbial biopesticides have a few challenges. Their performance in the field can be inconsistent, as environmental conditions such as UV radiation, rainfall, and temperature fluctuations often reduce efficacy (Chandler et al., 2011). However, these limitations are being addressed, and product shelf life is being increased by advancements in formulation technology, including encapsulation, oil-based carriers, and nanoparticle delivery systems (Kalia et al., 2023). As a result, microbial biopesticides continue to expand their footprint in both conventional and organic agriculture, offering safer, eco-friendly solutions to pest control.

Biochemical biopesticides

Biochemical biopesticides are a broad category of naturally occurring substances or their synthetic counterparts that affect the growth, behavior, or reproduction rather than causing direct toxicity. They are frequently regarded as important tools in sustainable agriculture due to their ecological safety and specificity and are increasingly incorporated into integrated pest management programs (Isman, 2020; Tadesse et al., 2024).

One of the most widely studied categories within this group is botanical extracts. Azadirachtin, for instance, is found in neem (Azadirachta indica), which acts as a feeding deterrent and disrupts insect molting and reproduction. Similarly, because of its neurotoxic effects on insect nervous systems, pyrethrum, which is derived from Chrysanthemum cinerariifolium, has been used as a natural insecticide for decades (Isman, 2020). Although they are used less frequently now due to safety concerns, other plant-derived compounds like rotenone demonstrate the long-standing use of botanicals in pest control (Pavela & Benelli, 2016).

Essential oils have also emerged as effective biopesticides. Oils extracted from clove, lemongrass, and eucalyptus have shown strong repellent, insecticidal, and antifungal activities. They are less likely to develop resistance owing to their various modes of action, which include membrane disruption, respiratory inhibition, and interference with neurotransmission (Regnault-Roger et al., 2012; Benelli et al., 2018). Furthermore, essential oils often leave minimal residues, making them suitable for organic farming systems.

Natural growth regulators like chitosan and brassinosteroids are gaining attention for their dual functions in promoting plant health and managing pests. Derived from chitin, chitosan can enhance crop resistance to abiotic stresses, inhibit fungal growth, and initiate plant defense responses (El Hadrami et al., 2010; Malerba & Cerana, 2016). Brassinosteroids, while primarily known as plant hormones, also enhance resistance against insect and pathogen attack through activation of systemic defense pathways (Nakashita et al., 2003).

The increasing array of biochemical biopesticides demonstrates their versatility in combating various pest pressures and promoting environmentally conscious crop production. However, variability in the concentration of active compounds, quick degradation in the field, and comparatively high production costs are still major obstacles (Pavela & Benelli, 2016). The stability and persistence of these compounds are being enhanced by emerging formulation techniques, such as encapsulation and nanoemulsion technologies, indicating that biochemical biopesticides will become increasingly significant in future crop protection systems.

Plant-incorporated protectants (PIPs)

Plant-incorporated protectants (PIPs) represent a distinct category of biopesticides in which plants are genetically engineered to produce pesticidal substances within their own tissues. PIPs offer continuous protection throughout the plant's lifecycle, eliminating the need for repeated pesticide applications and providing continuous protection throughout the plant’s lifecycle, in contrast to microbial or biochemical products that typically require external application (Ruiu, 2018; Tadesse et al., 2024).

The most widely adopted PIPs are those expressing Bt-derived proteins, particularly Cry and Vip toxins. These proteins specifically target insect pests by binding to receptors in the midgut, causing pore formation, cell lysis, and ultimately insect death. Nowadays, Bt cotton and Bt maize are grown extensively across several continents, contributing to integrated pest management strategies and significantly lowering the use of chemical insecticides (James, 2018; Chakraborty et al., 2022).

Other protein-based defenses have been incorporated into plants in addition to Bt. For instance, maize lines expressing the cysteine protease inhibitor Mir1-CP have shown resistance to fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) by disrupting insect digestive processes (Pechan et al., 2000). Such innovations demonstrate the potential of PIPs to expand pest resistance mechanisms beyond the classic Bt framework.

A more recent frontier is RNA interference (RNAi)-based PIPs, in which plants are engineered to produce double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) that silences essential pest genes. Targeting lepidopteran and coleopteran pests with this strategy has shown promising results; studies have shown that when insects eat plants that express dsRNA, their survival and feeding rates are significantly reduced (Joga et al., 2016; Mat Jalaluddin et al., 2019). New approaches to broad-spectrum biocontrol are being explored by testing RNAi-based tactics against plant-parasitic nematodes.

In addition, secondary metabolites derived from bacteria and fungi have been expressed in plants to broaden resistance profiles. For example, crop plants have been modified to produce genes encoding toxins from the bacteria Photorhabdus and Xenorhabdus, which may improve resistance to a variety of insect pests (Stock et al., 2017).

Despite these successes, the use of PIPs is not without controversy. Public acceptance, probable non-target impacts, and the emergence of pest resistance continue to be major obstacles to widespread adoption (Tabashnik & Carrière, 2017). To address these issues, commercial crops are utilizing resistance management techniques, such as pyramiding multiple genes and refuge planting. (Carrière et al., 2016). Furthermore, advances in gene-editing technologies, such as CRISPR/Cas, are expected to provide more precise and durable options for engineering PIPs in the future (Kanchiswamy, 2016).

Taken together, PIPs show how genetic engineering can offer reliable, focused, and long-lasting pest control solutions. While challenges remain, ongoing research and regulatory refinement suggest that PIPs will continue to play an important role in next-generation crop protection.

Nano- and formulated biopesticides

A significant limitation of many biopesticides is their short shelf life and inconsistent performance under field conditions. While rapid degradation can limit residual activity, environmental factors such as UV radiation, rainfall, and high temperatures often reduce efficacy. Recent studies have focused on advanced formulations and delivery systems based on nanotechnology to overcome these limitations and enhance the stability, accuracy, and efficacy of biopesticides (Kalia et al., 2023; Kumar et al., 2022).

Nanoformulations represent one of the most promising approaches. Biopesticides, such as plant extracts, microbial metabolites, or double-stranded RNA, can be encapsulated in nanocarriers to increase solubility, shield active ingredients from deterioration, and guarantee controlled release. For example, chitosan nanoparticles loaded with dsRNA have been shown to protect RNA molecules from enzymatic breakdown in insect guts, thereby enhancing RNA interference efficiency against pests such as Helicoverpa armigera (Kumar et al., 2022). The delivery of dsRNA targeting important developmental genes in Grapholita molesta has also been made feasible by polymer-based nanocarriers, which has a major negative impact on larval growth and reproduction (Quílez-Molina et al., 2024).

Nano-encapsulated botanical extracts and essential oils are becoming more popular in addition to RNAi applications. In comparison to traditional sprays, plant-derived oils such as neem and clove, when prepared as nanoemulsions, show better stability, increased penetration into insect cuticles, and prolonged activity (Ghormade et al., 2011; Benelli, 2018). Additionally, these nanoemulsions minimize environmental residues and application costs by enabling lower dosages without compromising efficacy.

Furthermore, formulation technology is essential in expanding the reach of microbial biopesticides. To increase the shelf life of bacterial and fungal products and make them easier to use in the field, encapsulated beads, wettable powders, and oil-based suspensions have been developed (Mascarin & Jaronski, 2016). Recent advances in UV protectants and carrier materials are further helping to stabilize sensitive organisms such as baculoviruses, making them more reliable under fluctuating environmental conditions (Haase et al., 2015).

The commercial use of nanopesticides and biopesticide formulations is still in the stages of development. Questions remain about large-scale production costs, regulatory approval, and potential risks of nanoparticle accumulation in the environment (Kalia et al., 2023). Nonetheless, the rapid progress in this area suggests that smart formulations will play an increasingly important role in overcoming the inherent limitations of traditional biopesticides, ultimately improving their consistency and effectiveness in real-world farming systems.

MODE OF ACTION OF BIOPESTICIDES

The effectiveness of biopesticides lies in their diverse and often highly specific mechanisms of action, which distinguish them from conventional synthetic pesticides. Rather than causing broad-spectrum toxicity, biopesticides typically target physiological processes in pests, making them safer for non-target organisms and the environment (Ruiu, 2018; Chandler et al., 2011).

The Cry and Vip proteins, for instance, are produced by bacterial agents like Bacillus thuringiensis and bind to receptors in the midgut of insects, resulting in pore formation, osmotic balance disruption, and ultimately larval death (Bravo et al., 2017; Chakraborty et al., 2022). Fungal pathogens like Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae exhibit a similar level of precision. They use degradative enzymes to penetrate through the insect's cuticle and multiply within the hemocoel, releasing toxins that quickly kill the host (Mascarin & Jaronski, 2016; Jaber & Ownley, 2018).

Viruses offer an additional strategy. Nucleopolyhedroviruses replicate inside insect cells, which results in systemic infections, larval disintegration, and the subsequent dissemination of viral particles throughout the environment (Haase et al., 2015; Erlandson, 2020). Entomopathogenic nematodes adopt a different but equally efficient approach, vectoring symbiotic bacteria such as Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus, which quickly establish lethal septicemia inside the host insect (Shapiro-Ilan et al., 2017).

Table 1. Table summarizing key biopesticides, their target pests or diseases, and modes of action in major crops.

Crop

Biocontrol Agent

Type

Target Pest/Disease

Mode of Action / Impact

Reference

Cotton, Maize, Rice, Vegetables

Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) Cry & Vip proteins

Microbial (Bacterium) / PIP

Lepidopteran, coleopteran, dipteran insects

Midgut binding → pore formation → larval death; incorporated in Bt cotton/maize → reduced insecticide use

(Bravo et al., 2017; Chakraborty et al., 2022)

Rice, Wheat, Tomato

Pseudomonas fluorescens

Microbial (Bacterium)

Soil-borne pathogens (Fusarium, Rhizoctonia, Pythium)

Antagonistic metabolites; induces systemic resistance

(Gupta & Dikshit, 2010; Oliveira et al., 2021)

Maize, Sorghum, Vegetables

Trichoderma harzianum

Microbial (Fungus)

Soil-borne fungal pathogens

Mycoparasitism, antibiotic production, ISR; also promotes growth

(Mascarin & Jaronski, 2016; Jaber & Ownley, 2018)

Vegetables, Fruits, Cereals

Beauveria bassiana, Metarhizium anisopliae

Microbial (Fungi)

Aphids, whiteflies, termites, beetles

Cuticle penetration → proliferation in hemocoel → insect death

(Mascarin & Jaronski, 2016; Jaber & Ownley, 2018)

Sugarcane, Cotton, Maize

Nucleopolyhedroviruses (NPVs), Granuloviruses (GVs)

Microbial (Viruses)

Lepidopteran larvae

Ingestion → systemic infection → larval liquefaction → horizontal spread

(Haase et al., 2015; Erlandson, 2020)

Vegetables, Ornamentals, Turf

Steinernema spp., Heterorhabditis spp. (with Xenorhabdus/Photorhabdus bacteria)

Microbial (Nematodes)

Soil-dwelling pests (cutworms, grubs, weevils)

Nematode invasion → bacterial release → septicemia → insect death

(Kaya et al., 2006; Shapiro-Ilan et al., 2017)

Cotton, Rice, Pulses

Neem (Azadirachtin)

Biochemical (Botanical)

Lepidopterans, sap-feeding insects

Feeding deterrent, molting disruption, reproductive inhibition

(Isman, 2020; Pavela & Benelli, 2016)

Vegetables, Fruits, Cereals

Pyrethrum (Chrysanthemum extract)

Biochemical (Botanical)

Aphids, thrips, beetles

Neurotoxic to insect nervous system

(Isman, 2020)

Various crops

Essential oils (clove, lemongrass, eucalyptus)

Biochemical

Insects, fungi

Repellence, membrane disruption, neurotoxicity

(Regnault-Roger et al., 2012; Benelli et al., 2018)

Maize

Mir1-CP (protease inhibitor expressed in transgenic maize)

PIP

Fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda)

Disrupts insect digestion → resistance

(Pechan et al., 2000)

Maize, Potato, Soybean

RNAi-based PIPs

PIP

Lepidopteran & coleopteran pests

dsRNA → gene silencing → impaired development & survival

(Joga et al., 2016; Mat Jalaluddin et al., 2019)

Other biopesticides function more by disrupting the behavior or development of pests rather than killing them. Compounds like azadirachtin from neem disrupt insect molting and reproduction while also deterring feeding, whereas essential oils such as clove and eucalyptus destabilize cell membranes and impair neurological function, producing strong repellent or toxic effects (Isman, 2020; Benelli et al., 2018). Instead of directly killing pests, semiochemicals such as sex pheromones used in mating disruption lower populations by preventing reproductive success (Witzgall et al., 2010).

Recent innovations increasingly rely on genetic engineering. Crops that express pesticidal proteins or double-stranded RNA molecules affect critical pest genes upon consumption, resulting in developmental arrest or mortality. This approach broadens the application of biopesticides from external application to integration within the plant system itself (Joga et al., 2016; Mat Jalaluddin et al., 2019).

These different mechanisms highlight the efficacy of biopesticides, as they utilize multiple modes of toxicity to target a spectrum of molecular, physiological, and behavioral weaknesses in pests. This diversity reduces unintended ecological consequences and provides opportunities to combine various products, enhancing efficacy and mitigating resistance development.

ADVANTAGES AND LIMITATIONS

The environmental safety of biopesticides represents a significant advantage. Due to their origin from natural organisms or compounds, these substances tend to decompose quickly and result in minimal residues in soil, water, or food products. This characteristic enhances their compatibility with organic farming systems and aligns with consumer preferences for residue-free produce (Gupta & Dikshit, 2010; Oliveira et al., 2021). Their high specificity is a notable strength, as most biopesticides target specific pests while leaving beneficial insects, pollinators, and natural enemies unharmed, thus promoting ecological balance and biodiversity in agroecosystems (Chandler et al., 2011; Jaber & Ownley, 2018). The diverse modes of action, including midgut disruption in insects and behavioral modification via pheromones, decrease the probability of rapid resistance development relative to synthetic pesticides, particularly when incorporated into integrated pest management programs (Bravo et al., 2017; Witzgall et al., 2010).

Also, biopesticides provide benefits that extend beyond mere pest control. Specific microbial agents, including Trichoderma spp. and Pseudomonas fluorescens, exhibit dual functions by controlling pathogens and promoting plant growth, as well as inducing systemic resistance, which enhances crop vigor and yield stability (El Hadrami et al., 2010; Junaid et al., 2020). Essential oils and chitosan, meanwhile, combine antimicrobial or insecticidal activity with the ability to enhance plant defense pathways, further highlighting their multifunctional benefits (Malerba & Cerana, 2016; Benelli et al., 2018).

Despite these strengths, the use of biopesticides is constrained by several limitations. Their efficacy is often less predictable than that of synthetic pesticides, vastly because environmental factors such as UV radiation, rainfall, and temperature fluctuations can reduce their persistence and effectiveness in the field (Chandler et al., 2011; Mascarin & Jaronski, 2016). The scalability of microbial products is further restricted by their short shelf life and the requirement for specific storage conditions, especially in areas with inadequate infrastructure (Shapiro-Ilan et al., 2017). Variability in active compound concentration is also a challenge for botanical extracts and essential oils, as factors like plant source, harvest time, and processing methods can significantly affect product consistency (Pavela & Benelli, 2016; Isman, 2020).

Economic and regulatory barriers add another layer of difficulty. Commercialization may be delayed by navigating complicated and occasionally contradictory regulatory frameworks, and biopesticide development frequently entails high research and production costs (Oliveira et al., 2021). Due to a lack of knowledge, inadequate training, or the belief that biopesticides are less effective than traditional chemicals, farmers may be reluctant to use them, especially in developing nations (Kalia et al., 2023).

Taken together, these benefits and drawbacks highlight the potential and difficulties of biopesticides in contemporary agriculture. Although their sustainability credentials and ecological advantages are indisputable, their full potential will depend on resolving adoption, cost, and stability concerns.

FUTURE PROSPECTS OF BIOPESTICIDES

Looking ahead, the future of biopesticides is closely tied to advances in biotechnology, formulation science, and integrated pest management strategies. One of the most promising fields is RNA interference (RNAi), which offers previously unprecedented precision in targeting vital genes of insects, nematodes, and even plant pathogens. RNAi may be able to resolve stability problems and make field-ready applications possible when paired with delivery systems based on nanotechnology (Joga et al., 2016; Kumar et al., 2022). The shelf life and field performance of microbial agents and botanical extracts are also anticipated to be significantly enhanced by advancements in encapsulation and controlled-release formulations, which will lower one of the primary adoption barriers (Ghormade et al., 2011; Kalia et al., 2023).

Another area of growth lies in the integration of biopesticides with digital agriculture and precision farming tools. More focused biopesticide applications could be explored with developments in remote sensing, pest forecasting, and decision-support systems, which would minimize waste and increase effectiveness (Chakraborty et al., 2022; Oliveira et al., 2021). At the same time, genome editing tools like CRISPR/Cas could help create new plant-based defenses and modified microorganisms that are more resilient and effective (Kanchiswamy, 2016; Tabashnik & Carrière, 2017).

Efforts to tackle socio-economic and regulatory issues will be equally essential. The widespread use of biopesticides will require incentives for adoption, standardized approval procedures, and expanded farmer training, especially in areas where chemical pesticides continue to dominate pest management (Oliveira et al., 2021; Tadesse et al., 2024). Biopesticides are positioned to play a bigger role in agriculture as it moves toward more climate-resilient and sustainable systems—not as alternatives to traditional methods, but as essential supplements.

REFERENCES

Benelli, G., Pavela, R., Canale, A., & Mehlhorn, H. (2018). Tick repellents and acaricides of botanical origin: A green roadmap to control tick-borne diseases? Parasitology Research, 117, 45–60.

Bravo, A., Likitvivatanavong, S., Gill, S. S., & Soberón, M. (2017). Bacillus thuringiensis: A story of a successful bioinsecticide. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 41, 423–431.

Carrière, Y., Crickmore, N., & Tabashnik, B. E. (2016). Optimizing pyramided transgenic Bt crops for sustainable pest management. Nature Biotechnology, 33, 161–168.

Chandler, D., Bailey, A. S., Tatchell, G. M., Davidson, G., Greaves, J., & Grant, W. P. (2011). The development, regulation and use of biopesticides for integrated pest management. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 366, 1987–1998.

Chakraborty, S., Newton, A. C., & Allard, R. W. (2022). Harnessing microbial biopesticides for sustainable agriculture. Frontiers in Agronomy, 4, 22–34.

El Hadrami, A., Adam, L. R., El Hadrami, I., & Daayf, F. (2010). Chitosan in plant protection. Marine Drugs, 8, 968–987.

Erlandson, M. (2020). Insect pest control by viruses. Canadian Entomologist, 152, 481–490.

Ghormade, V., Deshpande, M. V., & Paknikar, K. M. (2011). Perspectives for nano-biotechnology enabled protection and nutrition of plants. Biotechnology Advances, 29, 792–803.

Gupta, S., & Dikshit, A. K. (2010). Biopesticides: An eco-friendly approach for pest control. Journal of Biopesticides, 3, 186–188.

Haase, S., Sciocco-Cap, A., Romanowski, V., & Ferrelli, M. L. (2015). Baculovirus insecticides in Latin America: Historical overview, current status and future perspectives. Viruses, 7, 2230–2267.

Isman, M. B. (2020). Botanical insecticides in the twenty-first century: New horizons and old barriers. Annual Review of Entomology, 65, 233–249.

Jaber, L. R., & Ownley, B. H. (2018). Can we use entomopathogenic fungi as endophytes for dual biological control of insect pests and plant pathogens? Biological Control, 116, 36–45.

James, C. (2018). Global status of commercialized biotech/GM crops: 2018. ISAAA Briefs, 54, 1–123.

Joga, M. R., Zotti, M. J., Smagghe, G., & Christiaens, O. (2016). RNAi efficiency, systemic properties, and novel delivery methods for pest insect control: What we know so far. Frontiers in Physiology, 7, 553.

Junaid, J. M., Dar, N. A., Bhat, T. A., Bhat, A. H., & Bhat, M. A. (2020). Commercial biopesticides in plant disease management. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology, 23, 101485.

Kalia, A., Abd-Elsalam, K. A., & Kuca, K. (2023). Nano-biopesticides today and future perspectives. Frontiers in Plant Science, 14, 111–126.

Kanchiswamy, C. N. (2016). DNA-free genome editing methods for targeted crop improvement. Plant Cell Reports, 35, 1469–1474.

Kaya, H. K., & Gaugler, R. (2006). Entomopathogenic nematodes: Utility in IPM. Annual Review of Entomology, 38, 181–206.

Kumar, P., Pandey, P., Sharma, R., & Thakur, R. (2022). Nanotechnology interventions in sustainable agriculture: Recent advances and future prospects. Frontiers in Nanotechnology, 4, 855–868.

Malerba, M., & Cerana, R. (2016). Chitosan effects on plant systems. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 17, 996.

Mascarin, G. M., & Jaronski, S. T. (2016). The production and uses of Beauveria bassiana as a microbial insecticide. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 32, 177.

Mat Jalaluddin, N. S., Finka, A., & Golombek, A. J. (2019). RNAi in crop protection: Strategies and challenges. Plants, 8, 496.

Oliveira, B. M., Lima, F. V., & Moreira, J. M. (2021). Biopesticides: A promising alternative for sustainable agriculture. Journal of Cleaner Production, 316, 128147.

Pavela, R., & Benelli, G. (2016). Essential oils as ecofriendly biopesticides? Challenges and constraints. Trends in Plant Science, 21, 1000–1016.

Pechan, T., Ye, L., Chang, Y. M., Mitra, A., Lin, L., Davis, F. M., Williams, W. P., & Luthe, D. S. (2000). A unique 33-kD cysteine proteinase accumulates in response to larval feeding in maize genotypes resistant to fall armyworm. Plant Cell, 12, 1031–1040.

Quílez-Molina, A. I., González-González, E., Martínez-Guitián, M., & Vázquez, C. (2024). Nanocarrier-mediated delivery of dsRNA for sustainable pest management. Pest Management Science, 80, 1456–1470.

Regnault-Roger, C., Vincent, C., & Arnason, J. T. (2012). Essential oils in insect control: Low-risk products in a high-stakes world. Annual Review of Entomology, 57, 405–424.

Ruiu, L. (2018). Microbial biopesticides in agroecosystems. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 102, 2949–2954.

Shapiro-Ilan, D. I., Han, R., & Dolinski, C. (2017). Entomopathogenic nematode production and application technology. Journal of Nematology, 49, 1–17.

Stock, S. P., Rivera-Orduna, F. N., Flores-Lara, Y., & Flores-Lara, J. (2017). Heterorhabditis bacteriophora and its bacterial symbionts as potential sources of novel natural products. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 150, 1–12.

Tabashnik, B. E., & Carrière, Y. (2017). Surge in insect resistance to transgenic crops and prospects for sustainability. Nature Biotechnology, 35, 926–935.

Tadesse, T. M., Alemu, T., & Tesfaye, A. (2024). Biopesticides in sustainable agriculture: Trends and innovations. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 8, 155.

Vero, A., Giorgi, V., & Scariot, V. (2023). Microbial biopesticides in agroecosystems: Recent advances and perspectives. Microorganisms, 11, 203.

Witzgall, P., Kirsch, P., & Cork, A. (2010). Sex pheromones and their impact on pest management. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 36, 80–100.