ABSTRACT

Mycelial biomass yield of Trichoderma harzianum was examined on eight different culture media including Prosopis juliflora pods (PJP) + sabudana + potato extract, PJP + sabudana + maize starch (MS) extract, potato dextrose broth (PDB), PDB + sabudana + MS extract, PJP+ sabudana extract, sabudana extract, PJP extract and MS extract. These media had a significant effect on fresh and dry weight of mycelial mat of T. harzianum. PJP extract was the best medium out of all tested media due to the presence of high carbohydrate content and triacontanol, a growth hormone. The present investigation would be helpful in enhancing the conidial growth of T. harzianum during mass multiplication of biocontrol agent thus minimizing the cost of production as PJP pods are abundantly available freely in the environment.

Keywords: Trichoderma harzianum, Prosopis juliflora pods, mycelial mat, triacontanol

INTRODUCTION

Biological control entails harnessing one or more living organisms to manage pathogens or diseases. Microbial inoculants, serving as biocontrol agents, offer effective alternatives to mitigate the drawbacks associated with heavy reliance on chemical interventions (Nakkeeran et al., 2002). Among these agents one such fungal genus is Trichoderma, which are ubiquitous fungi thriving in soil and root environments. They exhibit saprophytic behavior, rapid growth, and are easily cultivable with extended shelf life. Notably, Trichoderma harzianum stands out as a highly promising bioagent combatting phytopathogenic fungi such as Fusarium oxysporum, Macrophomina phaseolina, and Sclerotinia sclerotium (Manczinger et al., 2002).

Use of liquid media is crucial in preliminary selection of T. harzianum for subsequent management of pathogen. Work was done to compare the efficacy of different liquid culture media using abundantly growing pods of mesquite (Prosopis juliflora (SW) DC.). Mesquite serves as a versatile tree of arid and semi-arid regions. Mature trees yield approximately 50 kg of pods annually which are non-palatable for human consumption. These pods boast of high carbohydrate content and contain the growth hormone triacontanol (Khan et al., 1992; Mawar and Mathur 2022). Earlier attempts have been made to utilize these pods as a substitute for chemical sugar sources in culture media for the growth of certain fungi (Santos and Pereria 1990). Based on available information, formulations of various culture media were attempted using Prosopis pods. The current studies aimed to ascertain the feasibility of this natural sugar source as a replacement for costly chemical alternatives and to determine the specific role of triacontanol as a supplement in media formulations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Procurement of Trichoderma harzianum

A research investigation was undertaken at Plant Pathology Laboratory of ICAR- Central Arid Zone Research Institute, Jodhpur, Rajasthan to explore the suitability of various liquid culture media (Elad et al., 1981; Iqbal et al., 2017) for isolating and cultivating T. harzianum, a native fungal biocontrol agent of ICAR-CAZRI namely Th MCC 1723. T. harzianum was multiplied on PDA plates through hyphal tip technique and preserved in the refrigerator at 4° C for further use.

Study of mycelial growth of fungi on different culture media

The growth of mycelial mat of T. harzianum was studied on eight different liquid media prepared with or without using Prosopis juliflora pods as a carbohydrate supplement (Lodha et al., 1999) in 1,000ml distilled water viz. 1. Prosopis juliflora pods (powdered PJP) (100g) + sabudana (30g)+ potato starch extract (PSE) (200g), 2. powdered PJP(100g) + sabudana (30g) + maize starch extract (MSE) (30g), 3. potato dextrose broth (PDB) (24g) (Himedia, India), 4. PDB(24g) + sabudana (30g)+ MSE (30g), 5. powdered PJP(100g)+ sabudana (30g), 6. sabudana (30g), 7. powdered PJP (100g) and 8. MSE (30g). The prepared media were sterilized in autoclave at 15 psi for 15 min at 121.6°C and poured in trays of dimensions 9”x12”. A 5mm disc of T. harzianum grown on PDA plates was cut with the help of cork borer and three discs were transferred to each tray containing different media. The trays were covered with aluminum foil and were incubated at 25°C for 15 days. Three replications were maintained. Data was recorded by measuring the fresh and dry weight of fungal biomass obtained after 15 days interval. The data was statistically analyzed using completely randomized design (CRD).

Population counts on Martin Rose Bengal Streptomycin Agar medium (MRBSA)

Colonies of T. harzianum were enumerated on Martin Rose Bengal Streptomycin Agar medium (Ejad and Chet, 1983) by serial dilution method. Three sub-samples (1 ml each) were taken from different liquid medium inoculated with T. harzianum were serially diluted at 10-10 on MRBSA medium after 15 days of furious growth. Three replications were maintained, and data was recorded after 7 days.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

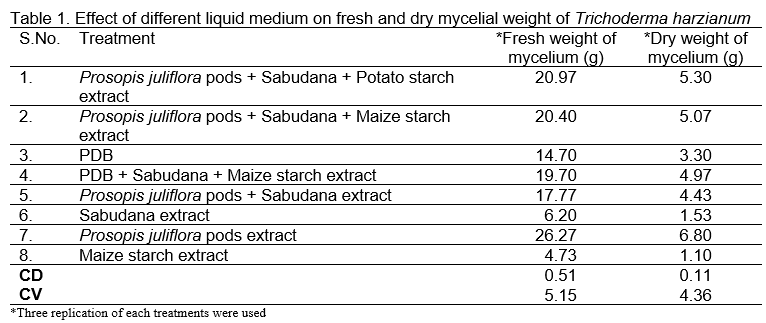

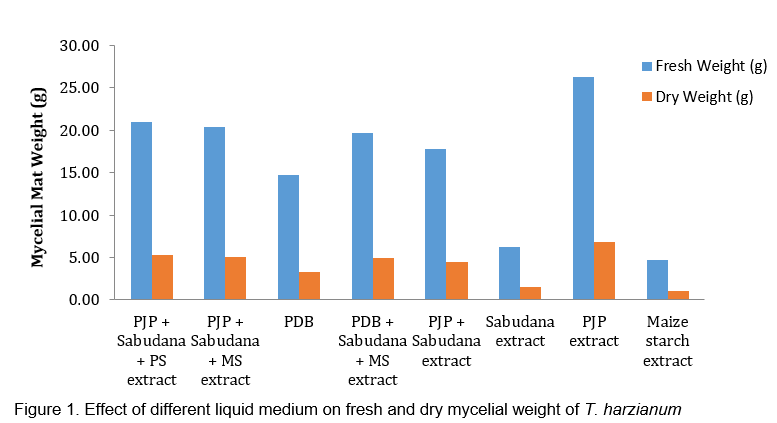

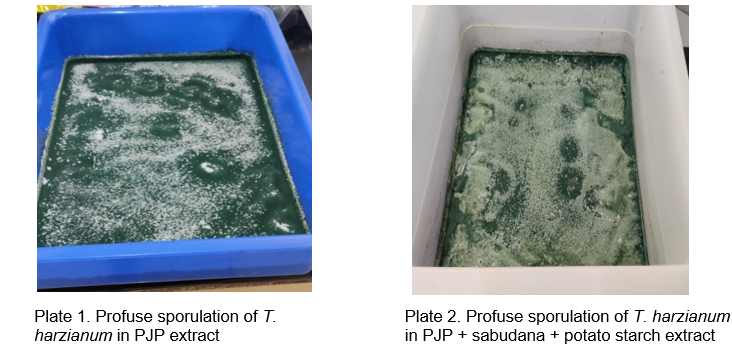

Investigations conducted to analyze the effectiveness of different culture media and to delineate their advantages and limitations regarding biocontrol agent fungal biomass yield revealed that supplementing decoction of Prosopis pods significantly enhanced the mycelial growth and sporulation of Trichoderma harzianum as compared to other medium. Also, from Table 1 and Figure 1 it could be deduced that when extract of Prosopis pods was used singly, maximum mycelial fresh and dry weight was observed (26.27g and 6.80g, respectively) followed by extract of Prosopis juliflora pods + sabudana + potato starch (20.97g and 5.30g, respectively). The least fresh and dry weight was observed in sabudana extract (6.20g and 1.53g, respectively).

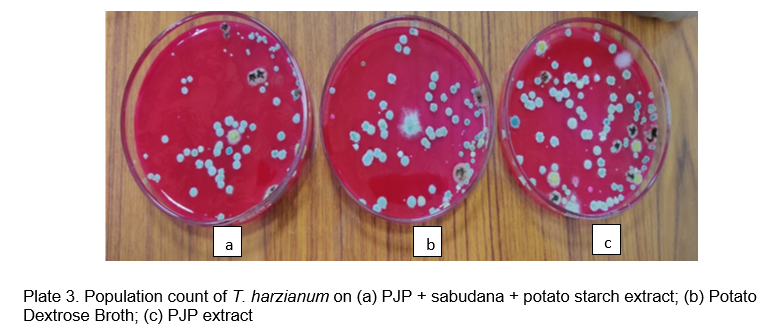

Also from Table 2, it could be concluded that population count of T. harzianum was found maximum in Prosopis juliflora pods extract (68.4×1010) followed by PDB (55.4×1010) than the combination of Prosopis juliflora pods + Sabudana + Potato starch extract (53.2×1010). However, the least count was recorded on sabudana extract (20.3×1010).

Globally, there is an ongoing effort to identify alternative sources of chemicals derived from natural plant products (Nene and Sheila, 1994). Understanding which plant products promote fungal growth is crucial for cultivating fungi efficiently in laboratory settings, thereby minimizing the dependence on synthetic chemicals. Research has explored the use of cassava starch as a carbohydrate source in agar culture media as a substitute for potatoes (Awuah, 1989). The enhanced growth of T. harzianum on Prosopis juliflora can largely be attributed to the high concentrations of sugars and other nutrients found in various parts of the plant (Lodha et al., 1999; Tewari et al., 2000). In 2003, the global availability of P. juliflora pods was estimated to be approximately 2–4 million tons (Sawal et al., 2004).

CONCLUSION

In this investigation, a decoction of P. juliflora pods notably boosted the growth of Trichoderma harzianum. Thus PJP can be used as an alternative for chemical sugars sources used for making media.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflict of interest(s) exists.

REFERENCES

Elad, Y. and Chet, I. (1983). Improved selective media for isolation of Trichoderma spp or Fusarium spp. Phytoparasitica.11: 55-58.

Nakkeeran S, Krishnamoorthy AS, Ramamoorthy V and Renukadevi P (2002) Microbial inoculants in plant disease control. J. Ecobiol. 14(2): 83-94.

Manczinger L, Antal Z and Kredics L (2002) Ecophysiology and breeding of Mycoparasitic strains (a review). Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hungarica, 49(1): 1-14.

Khan HA, Lodha V, Ghanim A (1992). Triacontanol from leaves of Prosopis cineraria and Prosopis juliflora. Trans. ISDT 17: 29-32.

Mawar R and Mathur T (2022) Enhancing survival and multiplication of Trichoderma harzianum by Prosopis juliflora based compost in Indian arid region. Indian Phytopath. 75: 1-9.

Santos GLC, Pereria MSV (1990) Utilization of P. juliflora as culture medium and as enriching source for phytopathogenic fungi culture. In: The Current State of Knowledge on Prosopis juliflora (Habbit, M. A. and Saavendra, J.C. eds.) FAO, Rome. 335-337 pp.

Elad Y, Chet I, Henis Y (1981). A selective medium for improving quantitative isolation of Trichoderma species from soil. 9: 59-67.

Iqbal S, Ashfaq M, Malik AH, Inam-ulhaq, Khan KS, Mathews P (2017) Isolation, preservation and revival of Trichoderma viride in culture media. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 5(3): 1640-1646.

Lodha S, Bohra MD, Harsh LN (1999) Evaluation of Prosopis pods as a source of' carbohydrate for enhancing the growth of soil borne fungi. 52: 24-27.

Nene YL, Sheila VK (1994) A potential substitute for agar in routine cultural work on fungi and Bacteria. Indian. J. Mycol. Plant Pathol. 24: 159-163.

Awuah T (1989) Preparation and evaluation of dehydrated mycological media from West African raw materials. Ann. appl. Bioi. 115: 51-55.

Tewari JC, Harris PJC, Harsh L.N, Cadoret K, Pasiecznik NM (2000) Managing Prosopis julifora (Vilayati babul) –A technical manual. CAZRI, Jodhpur, India.

Sawal R. K,Ram Ratan and Yadav S. B. S (2004). Mesquite (Prosopis juliflora) Pods as a Feed Resource for Livestock- A Review. Asian-Aust. J. Anim. Sci. 17, : 719-725

Assessment of Prosopis juliflora Pods as a Carbohydrate Source for Optimizing the Growth of Biocontrol Agent Trichoderma harzianum

ABSTRACT

Mycelial biomass yield of Trichoderma harzianum was examined on eight different culture media including Prosopis juliflora pods (PJP) + sabudana + potato extract, PJP + sabudana + maize starch (MS) extract, potato dextrose broth (PDB), PDB + sabudana + MS extract, PJP+ sabudana extract, sabudana extract, PJP extract and MS extract. These media had a significant effect on fresh and dry weight of mycelial mat of T. harzianum. PJP extract was the best medium out of all tested media due to the presence of high carbohydrate content and triacontanol, a growth hormone. The present investigation would be helpful in enhancing the conidial growth of T. harzianum during mass multiplication of biocontrol agent thus minimizing the cost of production as PJP pods are abundantly available freely in the environment.

Keywords: Trichoderma harzianum, Prosopis juliflora pods, mycelial mat, triacontanol

INTRODUCTION

Biological control entails harnessing one or more living organisms to manage pathogens or diseases. Microbial inoculants, serving as biocontrol agents, offer effective alternatives to mitigate the drawbacks associated with heavy reliance on chemical interventions (Nakkeeran et al., 2002). Among these agents one such fungal genus is Trichoderma, which are ubiquitous fungi thriving in soil and root environments. They exhibit saprophytic behavior, rapid growth, and are easily cultivable with extended shelf life. Notably, Trichoderma harzianum stands out as a highly promising bioagent combatting phytopathogenic fungi such as Fusarium oxysporum, Macrophomina phaseolina, and Sclerotinia sclerotium (Manczinger et al., 2002).

Use of liquid media is crucial in preliminary selection of T. harzianum for subsequent management of pathogen. Work was done to compare the efficacy of different liquid culture media using abundantly growing pods of mesquite (Prosopis juliflora (SW) DC.). Mesquite serves as a versatile tree of arid and semi-arid regions. Mature trees yield approximately 50 kg of pods annually which are non-palatable for human consumption. These pods boast of high carbohydrate content and contain the growth hormone triacontanol (Khan et al., 1992; Mawar and Mathur 2022). Earlier attempts have been made to utilize these pods as a substitute for chemical sugar sources in culture media for the growth of certain fungi (Santos and Pereria 1990). Based on available information, formulations of various culture media were attempted using Prosopis pods. The current studies aimed to ascertain the feasibility of this natural sugar source as a replacement for costly chemical alternatives and to determine the specific role of triacontanol as a supplement in media formulations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Procurement of Trichoderma harzianum

A research investigation was undertaken at Plant Pathology Laboratory of ICAR- Central Arid Zone Research Institute, Jodhpur, Rajasthan to explore the suitability of various liquid culture media (Elad et al., 1981; Iqbal et al., 2017) for isolating and cultivating T. harzianum, a native fungal biocontrol agent of ICAR-CAZRI namely Th MCC 1723. T. harzianum was multiplied on PDA plates through hyphal tip technique and preserved in the refrigerator at 4° C for further use.

Study of mycelial growth of fungi on different culture media

The growth of mycelial mat of T. harzianum was studied on eight different liquid media prepared with or without using Prosopis juliflora pods as a carbohydrate supplement (Lodha et al., 1999) in 1,000ml distilled water viz. 1. Prosopis juliflora pods (powdered PJP) (100g) + sabudana (30g)+ potato starch extract (PSE) (200g), 2. powdered PJP(100g) + sabudana (30g) + maize starch extract (MSE) (30g), 3. potato dextrose broth (PDB) (24g) (Himedia, India), 4. PDB(24g) + sabudana (30g)+ MSE (30g), 5. powdered PJP(100g)+ sabudana (30g), 6. sabudana (30g), 7. powdered PJP (100g) and 8. MSE (30g). The prepared media were sterilized in autoclave at 15 psi for 15 min at 121.6°C and poured in trays of dimensions 9”x12”. A 5mm disc of T. harzianum grown on PDA plates was cut with the help of cork borer and three discs were transferred to each tray containing different media. The trays were covered with aluminum foil and were incubated at 25°C for 15 days. Three replications were maintained. Data was recorded by measuring the fresh and dry weight of fungal biomass obtained after 15 days interval. The data was statistically analyzed using completely randomized design (CRD).

Population counts on Martin Rose Bengal Streptomycin Agar medium (MRBSA)

Colonies of T. harzianum were enumerated on Martin Rose Bengal Streptomycin Agar medium (Ejad and Chet, 1983) by serial dilution method. Three sub-samples (1 ml each) were taken from different liquid medium inoculated with T. harzianum were serially diluted at 10-10 on MRBSA medium after 15 days of furious growth. Three replications were maintained, and data was recorded after 7 days.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Investigations conducted to analyze the effectiveness of different culture media and to delineate their advantages and limitations regarding biocontrol agent fungal biomass yield revealed that supplementing decoction of Prosopis pods significantly enhanced the mycelial growth and sporulation of Trichoderma harzianum as compared to other medium. Also, from Table 1 and Figure 1 it could be deduced that when extract of Prosopis pods was used singly, maximum mycelial fresh and dry weight was observed (26.27g and 6.80g, respectively) followed by extract of Prosopis juliflora pods + sabudana + potato starch (20.97g and 5.30g, respectively). The least fresh and dry weight was observed in sabudana extract (6.20g and 1.53g, respectively).

Also from Table 2, it could be concluded that population count of T. harzianum was found maximum in Prosopis juliflora pods extract (68.4×1010) followed by PDB (55.4×1010) than the combination of Prosopis juliflora pods + Sabudana + Potato starch extract (53.2×1010). However, the least count was recorded on sabudana extract (20.3×1010).

Globally, there is an ongoing effort to identify alternative sources of chemicals derived from natural plant products (Nene and Sheila, 1994). Understanding which plant products promote fungal growth is crucial for cultivating fungi efficiently in laboratory settings, thereby minimizing the dependence on synthetic chemicals. Research has explored the use of cassava starch as a carbohydrate source in agar culture media as a substitute for potatoes (Awuah, 1989). The enhanced growth of T. harzianum on Prosopis juliflora can largely be attributed to the high concentrations of sugars and other nutrients found in various parts of the plant (Lodha et al., 1999; Tewari et al., 2000). In 2003, the global availability of P. juliflora pods was estimated to be approximately 2–4 million tons (Sawal et al., 2004).

CONCLUSION

In this investigation, a decoction of P. juliflora pods notably boosted the growth of Trichoderma harzianum. Thus PJP can be used as an alternative for chemical sugars sources used for making media.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflict of interest(s) exists.

REFERENCES

Elad, Y. and Chet, I. (1983). Improved selective media for isolation of Trichoderma spp or Fusarium spp. Phytoparasitica.11: 55-58.

Nakkeeran S, Krishnamoorthy AS, Ramamoorthy V and Renukadevi P (2002) Microbial inoculants in plant disease control. J. Ecobiol. 14(2): 83-94.

Manczinger L, Antal Z and Kredics L (2002) Ecophysiology and breeding of Mycoparasitic strains (a review). Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hungarica, 49(1): 1-14.

Khan HA, Lodha V, Ghanim A (1992). Triacontanol from leaves of Prosopis cineraria and Prosopis juliflora. Trans. ISDT 17: 29-32.

Mawar R and Mathur T (2022) Enhancing survival and multiplication of Trichoderma harzianum by Prosopis juliflora based compost in Indian arid region. Indian Phytopath. 75: 1-9.

Santos GLC, Pereria MSV (1990) Utilization of P. juliflora as culture medium and as enriching source for phytopathogenic fungi culture. In: The Current State of Knowledge on Prosopis juliflora (Habbit, M. A. and Saavendra, J.C. eds.) FAO, Rome. 335-337 pp.

Elad Y, Chet I, Henis Y (1981). A selective medium for improving quantitative isolation of Trichoderma species from soil. 9: 59-67.

Iqbal S, Ashfaq M, Malik AH, Inam-ulhaq, Khan KS, Mathews P (2017) Isolation, preservation and revival of Trichoderma viride in culture media. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 5(3): 1640-1646.

Lodha S, Bohra MD, Harsh LN (1999) Evaluation of Prosopis pods as a source of' carbohydrate for enhancing the growth of soil borne fungi. 52: 24-27.

Nene YL, Sheila VK (1994) A potential substitute for agar in routine cultural work on fungi and Bacteria. Indian. J. Mycol. Plant Pathol. 24: 159-163.

Awuah T (1989) Preparation and evaluation of dehydrated mycological media from West African raw materials. Ann. appl. Bioi. 115: 51-55.

Tewari JC, Harris PJC, Harsh L.N, Cadoret K, Pasiecznik NM (2000) Managing Prosopis julifora (Vilayati babul) –A technical manual. CAZRI, Jodhpur, India.

Sawal R. K,Ram Ratan and Yadav S. B. S (2004). Mesquite (Prosopis juliflora) Pods as a Feed Resource for Livestock- A Review. Asian-Aust. J. Anim. Sci. 17, : 719-725