DOI: https://doi.org/10.56669/NECZ9831

ABSTRACT

The exact definition of biostimulants remains debated, with no universal agreement on what should or shouldn’t be included in this category. For example, certain microbes, such as Azotobacter, Rhizobium, and Azospirillum, are considered plant microbial biostimulants in Europe, whereas in India, they are classified as biofertilizers. Both the European Union and India have official definitions for biostimulants; however, countries such as the USA, China, Brazil, and Mexico tend to categorize biostimulants under broader terms, including soil amendments, plant growth regulators, or organic inputs. The most widely accepted definition describes biostimulants as substances, microorganisms, or mixtures of both applied to plants, seeds, or the root zone (rhizosphere) to stimulate the plant's natural processes.

Keywords: Biostiumlants, sustainable farming, biofertilizers, smart agriculture

INTRODUCTION

Biostimulants are made from natural materials such as extracts from plants, seaweed, microbial cultures, organic residues, and other by-products, providing an environmentally safe substitute for synthetic agricultural inputs (Anand et al., 2018; Singh et al., 2018). The 2018 U.S. Farm Bill defines biostimulants as substances or microbes that promote plant growth by enhancing nutrient uptake, efficiency, stress resilience, or yield, including organisms such as Rhizobium, Trichoderma, Bacillus, and Pseudomonas, as long as no pest control claims are made. In Canada, biostimulants are regulated under the Fertilizers Act; however, current rules prevent dual claims for both nutrition and protection. The EU recognizes only four microbial species—Azotobacter, Azospirillum, Rhizobium, and mycorrhizae—excluding microbial consortia. In contrast, India permits consortia under the Fertilizer Control Order (FCO) and enforces separate regulations for biofertilizers and biopesticides. While the U.S. and EU define biostimulants based on plant responses, India focuses on microbial functionality. Globally, definitions vary, with no unified consensus; for instance, microbes considered biostimulants in Europe may be categorized as biofertilizers in India (Mawar et al., 2021; 2023). Both the European Union and India have official definitions for biostimulants; however, countries such as the U.S., China, Brazil, and Mexico tend to categorize biostimulants under broader terms, including soil amendments, plant growth regulators, or organic inputs. The most widely accepted definition describes biostimulants as substances, microorganisms, or mixtures of both, applied to plants, seeds, or the root zone (rhizosphere) to stimulate the plant’s natural processes (Figure 1). This stimulation happens regardless of the product’s nutrient content. It aims to improve one or more of the following: (i) nutrient use efficiency, (ii) tolerance to environmental stresses, (iii) crop yield and quality, and (iv) availability of nutrients in the soil or rhizosphere. (Jardin 2015).

Why was biostimulant needed?

The introduction of high-yielding crop varieties has significantly increased agricultural output and food production. However, these crops require more water and agrochemicals, such as fertilizers and pesticides, to reach their full yield potential. This growing dependence on chemicals and groundwater is causing harm to natural resources, including soil health, water supplies, farm biodiversity, and the environment (Campbell et al., 2017; Power et al., 2010). Moreover, the overuse and careless application of these chemicals have led to a decline in the quality of food and animal feed, which negatively affects human and animal health. Additionally, the benefits from using more fertilizers are decreasing, resulting in slower growth in crop production and higher farming expenses. For example, in developing countries, the annual increase in food grain yields dropped from 1.71% during 1981–2000 to 1.43% during 2001–2020, even though fertilizer use rose from 40 to 55 kg per hectare (FAOSTAT). Climate change poses a serious challenge to the long-term sustainability of farming. Studies estimate that since 1961, climate change has slowed the growth of global agricultural productivity by approximately 21%, with developing countries being the most affected. (Ortiz-Bobea et al., 2021) In India, research shows that despite advances in technology, climate change has reduced agricultural productivity growth by roughly 25% since Birthal et al., 2021). Biostimulants are believed to provide multiple advantages, such as protecting natural resources, helping crops cope with stress from pests and environmental factors, and lowering production cost-all without harming crop yields (Van et al., 2022).

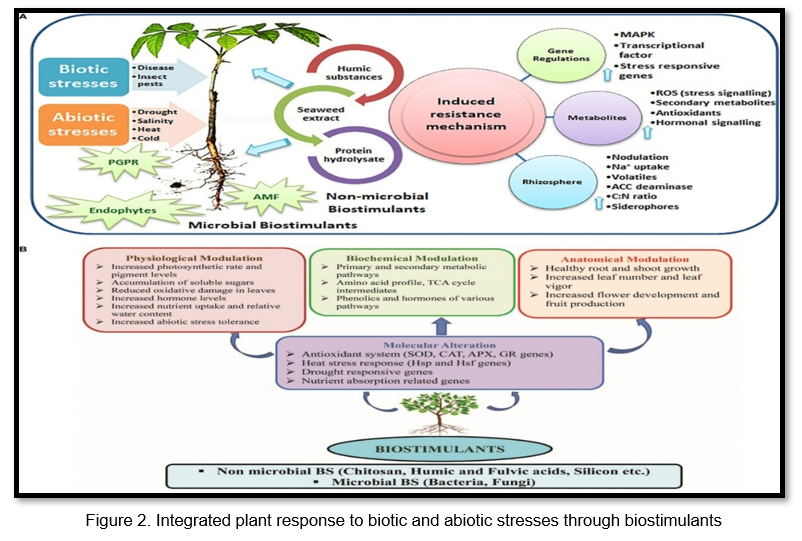

Biostimulants don’t provide nutrients or directly fight pests and diseases. Instead, they activate natural processes inside the plants and the beneficial microbes in the soil (Jardin 2015; Sharma et al.2014). By causing changes at the molecular level and affecting the plant’s physiology, biochemistry, and structure, biostimulants help plants better resist stress caused by pests, diseases, and environmental conditions

IMPACT OF BIOSTIMULANTS

Crop yields and quality traits

Biostimulants enhance plant growth and crop yields by affecting the plant’s natural processes. They promote the development of roots and shoots, increase organic carbon levels, improve nutrient exchange and nitrogen use, stimulate beneficial soil microbes, boost the plant’s antioxidant defenses, and help plants retain water more effectively (Carillo et al., 2019; Arslan et al., 2021). According to a meta-analysis, applying various biostimulants leads to an increase in crop yields ranging from 15% to 17%. Foliar spraying with seaweed extracts from Kappaphycus alvarezii and Gracilaria edulis has been shown to boost maize yields by approximately 18.5% and 26%, respectively (Basavaraja et al., 2018). The use of biostimulants, such as amino acids and yeast extract, resulted in yield increases of 8.5% and 20%, respectively, in off-season corn grown under water-stress conditions (Da Silva et al., 2017). In dry and semi-dry areas, using seaweed extract, humic and fulvic acids, chitosan, and plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) was shown to improve crop yields by 8.5% during moderate water stress and by 11.4% under severe water stress (Mullany M., 2024). Seaweed extract applied at a 15% concentration enhanced maize net returns by between 7.7% and 16.5% (Singh et al., 2016). Additionally, research has shown that biostimulants can enhance the nutritional quality of crops (Suman et al., 2017). Foliar application of seaweed extract derived from Kappaphycus alvarezii significantly improved the nutrient content in soybean grains, increasing nitrogen by 36%, phosphorus by 61%, potassium by 49%, and sulfur by 93% (Rathore et al., 2009). Seaweed-based biostimulants contain natural plant hormones such as auxin, cytokinin, kinetin, zeatin, gibberellins, glycine betaine, and choline chloride. These compounds promote plant growth and help crops withstand environmental stress by speeding up the movement of nutrients from leaves to stems and boosting the production of photosynthetic pigments (Gupta et al., 2021). Therefore, biostimulants play an important role in improving nutritional quality while reducing the use of chemical inputs and lessening harmful environmental impacts.

Nutrient use efficiency (NUE)

The use of biostimulants has been shown to improve nutrient use efficiency (NUE) and reduce the need for fertilizers, lowering production costs (Brown et al., 2015). For instance, applying amino acids like Terramin Pro increased NUE in wheat by 28% (Laurent et al., 2020), while protein hydrolysates boosted it by 12.9% in spinach and seaweed extracts raised it by 16% in rapeseed and wheat (Ziomek et al., 2019). Applying seaweed extracts to maize notably boosted nutrient absorption. Extract from Kappaphycus alvarezii lead to increases of 31% in nitrogen (N), 38% in phosphorus (P), and 28% in potassium (K) uptake. Similarly, Gracilaria edulis extract enhanced N, P, and K uptake by 23%, 41%, and 26%, respectively (Basavaraja et al., 2018). The use of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) enhances nutrient use efficiency by improving nutrient uptake, facilitating nitrogen fixation, and promoting nutrient mobility in the soil, particularly under stress conditions. For instance, inoculating green gram seeds with PGPR led to increased N, P, and K uptake by 17%, 21%, and 23%, respectively, contributing to improved crop productivity (Kumar et al., 2020; Yadav et al., 2014). It is also widely recognized that strong root growth is essential for plants to absorb nutrients effectively. Many studies have found that using biostimulants encourages better root development, enabling plants to explore the soil more thoroughly and take up nutrients more efficiently (Bhupenchandra et al., 2022; Rouphael et al., 2017). Biostimulant application modifies the soil’s microbial structure and enhances enzymatic activity, facilitating faster humus development and improving the soil’s ability to store carbon (Singh et al., 2018). Additionally, biostimulants can improve nutrient availability, uptake, and transport within plants by stimulating H⁺-ATPase enzyme activity. This leads to increased hydrogen ion release from the roots, resulting in a lower pH in the surrounding root zone (Canellas et al., 2002).

Response to abiotic stress

Biostimulants help plants become more resistant or tolerant to environmental stresses like drought. Acadian Plant Health has introduced ASM, an advanced seed treatment that offers dual protection by enhancing resistance to both biotic stresses (pests and diseases) and abiotic stresses like drought, heat, and cold (Figure 2). It combines Acadian’s proprietary seaweed extract with a synergistic active ingredient to strengthen early plant development. ASM enhances root and shoot growth, enabling crops to tolerate environmental stress better. A yield increase of up to 16% in maize under drought, 28–35% more root biomass in soybeans, and a yield increase of up to 16% in maize under drought, as well as a yield improvement of up to 6.4% across regions (Acadian Plant Health, 2025). In wheat and corn, ASM also activated stress-response genes, confirming its effectiveness at the molecular level. Importantly, it showed no negative impact on germination or seedling uniformity, ensuring safe and reliable early crop performance (Acadian Plant Health, 2025). Research has shown that biostimulants protect crops such as maize (Ertani et al., 2013), tomato (Petrozza et al., 2014), wheat, and other horticultural plants (Irani et al., 2021) from drought stress. Seaweed extracts help plants use water more efficiently and increase crop production during drought stress (Bhupenchandra et al., 2022). Further, humic acid has been shown to help tomatoes and bell peppers tolerate heat stress (Gomes et al., 2019). Seaweed extracts have been found to reduce the impact of nutrient deficiencies during cold weather (Van et al., 2017; Tursun, 2022). Similarly, other research indicates that biostimulants can help plants cope with challenges such as low rainfall and extreme temperature conditions. Salinity stress is a big problem for farming, especially in dry, semi-dry, and coastal areas. Spraying biostimulants, such as humic acid, glycine betaine, and chitosan, on leaves helps mitigate the harmful effects of salt stress in crops like wheat, maize, and barley. Biostimulants enhance photosynthetic efficiency and improve plant water relations by regulating stomatal conductance, maintaining leaf relative water content, and improving cellular osmotic adjustment. (Rakkammal et al., 2023; Meena et al., 2025). They also reduce cell damage, increase protective compounds like proline, lower harmful molecules called reactive oxygen species (ROS) and improve antioxidant enzyme activity (Figure 2). All these effects help plants better handle stress from their environment (Rabelo et al., 2019; Hafez et al., 2020). Biostimulants help plants cope with environmental stress by triggering the production of protective compounds like heat shock proteins, phenolics, amino acids, organic acids, dehydrins, and ACC-deaminase. Application of humic acid and seaweed extract has been shown to activate drought-responsive genes, enhancing photosynthetic efficiency, improving water retention capacity, and optimizing stomatal regulation under drought stress conditions (Khan et al., 2020).

Response to biotic stress

Biostimulants play a crucial role in enhancing plant resistance to biotic stresses by activating innate defense mechanisms and strengthening host–pathogen interactions. They stimulate the synthesis of defense-related compounds such as phenolics, heat shock proteins, amino acids, organic acids, dehydrins, and enzymes associated with induced systemic resistance (ISR), including ACC-deaminase, which helps regulate stress-induced ethylene levels. Microbial biostimulants, particularly Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus pumilus, have been shown to enhance plant tolerance to pathogen attack by modulating key metabolic pathways such as ascorbate–aldarate metabolism, glyoxylate and dicarboxylate cycles, and sugar transformation processes, thereby improving cellular redox balance and defense readiness (Akbar et al., 2022). Biostimulants also improve rhizosphere health by promoting beneficial microbial communities that compete with or suppress phytopathogens through mechanisms such as antibiosis, competition for nutrients and space, and mycoparasitism. Widely used microbial biostimulants, including Trichoderma spp., Bacillus subtilis, and Pseudomonas fluorescens, act as effective biological antagonists against soil- and foliar-borne pathogens while simultaneously enhancing root architecture, nutrient uptake, and plant vigor (Backer et al., 2018). In addition, non-microbial biostimulants such as seaweed extracts and chitosan function as elicitors of plant defense, triggering systemic acquired resistance (SAR) and reinforcing cell wall integrity, thereby reducing pathogen penetration and colonization. Other inputs, including silicon and protein hydrolysates, further strengthen physical and biochemical barriers by enhancing lignification, enzyme activity, and overall metabolic efficiency, leading to improved disease resistance (Table 1). For optimal disease suppression, biostimulants are most effective when applied preventively, prior to pathogen establishment, and are increasingly integrated into holistic pest and disease management strategies as sustainable alternatives or complements to chemical control measures (Calvo et al., 2014; Povero et al., 2016).

Table 1. Examples of biostimulants for biotic stresses

|

Type

|

Examples

|

Mode of action

|

|

Microbial biostimulants

|

Trichoderma spp., Bacillus subtilis, P. fluorescens

|

Antagonize pathogens, trigger ISR

|

|

Seaweed extracts

|

Ascophyllum nodosum, Ecklonia maxima

|

Contain bioactive compounds that boost immunity

|

|

Protein hydrolysates

|

Enzymatically hydrolyzed soy and animal proteins

|

Improve metabolic activity and stress tolerance

|

|

Chitosan

|

Derived from crustacean shells

|

Triggers SAR, strengthens cell walls

|

|

Silicon

|

Potassium silicate, sodium silicate

|

Reinforces cell walls, primes defense responses

|

How biostimulants work against biotic stresses: Biostimulants play a vital role in helping crops combat biotic stresses by enhancing natural plant defenses and improving overall plant health. They can induce systemic resistance by activating immune responses such as Systemic Acquired Resistance (SAR) or Induced Systemic Resistance (ISR), making plants more resilient to pathogen attacks (Figure 2). Biostimulants also enhance the soil microbiome by promoting beneficial microbes that can out compete harmful pathogens. Moreover, they help reduce oxidative stress by increasing antioxidant levels, which protects plant cells from damage during infection, for example, in rice, products like Chitoplant (chitosan) and Biozyme® (seaweed + amino acids) enhance immunity and root development, while Trichoderma viride controls fungal diseases. In tomatoes, Actosol® (humic acid) strengthens roots, Neemazal manages pests, and Biovita boosts resistance. Trichoderma harzianum is used for root disease prevention. For grapes, Kelpak® and chitosan sprays reduce fungal infections, and Bacillus subtilis protects leaves. In maize, Fulvital (fulvic acid) improves nutrient uptake, Bioguard (Bacillus spp.) protects roots, and AminoX aids plant recovery. These biostimulants offer a natural way to manage crop diseases effectively.

Factors affecting the effectiveness of biostimulant: The effectiveness of biostimulants in agriculture is influenced by several factors, including plant-related, environmental, and biostimulant-specific variables. Plant factors like species, growth stage, health status, and genetic makeup determine responsiveness, with stressed or nutrient-deficient plants often being more sensitive. The plant’s developmental stage such as seedling, vegetative, flowering, or fruiting also influences its need for biostimulants. Environmental factors such as soil type, pH, temperature, and light intensity are crucial, as they affect nutrient retention, microbial activity, and biostimulant performance. Extreme weather conditions or abiotic stresses like drought or salinity can enhance biostimulant effectiveness in certain cases. Biostimulant-related factors like formulation quality, concentration, application method, and frequency are also key to maximizing benefits. Proper formulation, dosage, and methods of application whether foliar spray, soil drench, or seed treatment are necessary for optimal absorption and distribution. Ultimately, when utilizing microbial biostimulants, the soil microbiome, competition from native microbes, and compatibility with soil conditions can either enhance or mitigate microbial performance. Adding synergistic substances, such as organic matter, can further enhance microbial survival and efficiency, enabling biostimulants to achieve their full potential in boosting plant growth and resilience.

Development of Biostimulants: The development of biostimulants involves a systematic process of identifying, formulating, and testing substances or microorganisms that enhance plant growth, nutrient efficiency, and stress tolerance, without being classified as fertilizers or pesticides. It begins with the identification of potential active ingredients from natural sources such as seaweeds, plant extracts, microbial strains (e.g., Bacillus, Azospirillum), humic substances, amino acids, or other organic compounds. These sources are screened in laboratory conditions for their ability to improve plant physiological processes like nutrient uptake, root development, photosynthesis, or resistance to abiotic stresses such as drought, salinity, and heat (Jardin., 2015). Once promising candidates are identified, formulation development follows. This step focuses on creating a stable, user-friendly product with consistent efficacy. It involves optimizing the concentration of active ingredients, selecting suitable carriers or additives, and determining the most effective form of application (e.g., foliar spray, soil drench, seed coating). During this stage, compatibility with fertilizers and other agrochemicals is also evaluated to ensure the product can be integrated into standard agricultural practices (Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, 2021c).

In India, the registration of biostimulants is governed by the Fertilizer Control Order (FCO), 1985, which was amended in 2021 to include biostimulants as a recognized category. The process begins with the classification of the biostimulant into one of the approved categories such as botanical extracts, seaweed extracts, humic substances, amino acids, or microbial formulations. Manufacturers must first apply for provisional registration by submitting Form G-1, which includes details about the product's composition, manufacturing process, and a certificate of analysis (CoA). Additionally, field trial data from at least two locations demonstrating the product's efficacy must be provided. Provisional registration is typically valid for two years, during which time further studies are conducted. To obtain final registration, manufacturers must submit Form G-2 along with a comprehensive dossier that includes detailed chemical composition, toxicological studies, bio-efficacy trials conducted across different agro-climatic zones, and analyses for heavy metals and pesticide residues. These studies must adhere to the OECD guidelines and be conducted at GLP-certified laboratories. Once the product meets all regulatory requirements and passes the necessary trials, it is granted final registration, allowing for commercialization. The product’s label claims, such as improved plant growth or stress tolerance, must be backed by scientific evidence. Regulatory fees are applicable for both provisional and final registration, and these can vary. The process is overseen by the Department of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, with evaluations conducted by the Central Biostimulant Committee. After registration, the product can be marketed across India, offering farmers sustainable solutions to enhance crop productivity and resilience (Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, 2021d).

Commercialization of biostimulants: The commercialization of biostimulants involves taking a scientifically validated and registered product to market with a focus on production, distribution, and farmer adoption. After regulatory approval, manufacturers scale up production with strict quality control to ensure consistency. Target crops and regions are identified where the product can address specific farming challenges, such as poor growth or stress conditions. Field trials and demonstrations help build trust by showing clear results under real farming conditions. Effective marketing highlights the product’s benefits and returns on investment, while distribution is handled through agri-input dealers, cooperatives, and digital platforms. Farmer training and support further drive adoption. Successful commercialization depends on scientific credibility, strategic outreach, and strong farmer engagement.

Legislations related biostimulants: In India, biostimulants are regulated under the Fertiliser (Control) Order, 1985 (FCO), which was amended in February 2021 to formally define and include biostimulants as a distinct category of agricultural inputs. The amendment introduced Clause 20C (which lays down the process for registration), Clause 38A (for the establishment of a Central Biostimulant Committee), and a new Schedule VI which contains detailed specifications for various types of biostimulants such as humic acid, seaweed extract, amino acid formulations, microbial products, and more (Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare, 2021a).

To market a biostimulant, companies must follow a two-step regulatory process. Initially, a provisional registration can be obtained by submitting Form G, which includes composition details, lab test reports, acute toxicity and eco-toxicity data, bio-efficacy trials in at least two agro-climatic zones, and validated analytical methods. Companies using this route must comply with the latest deadline as per the Second Amendment Order, 2025. Final approval and permanent inclusion in Schedule VI require the submission and review of complete data by the Central Biostimulant Committee. Approved products must meet strict contaminant limits identical to European Union (EU) standards—for example, limits for Pb (120 mg/kg), Cd (1.5 mg/kg), and As (40 mg/kg). Labels must clearly display the product name, composition, application rate, claimed benefits, and a disclaimer noting approval under the FCO. Enforcement is carried out by state fertilizer inspectors and notified testing laboratories. Non-compliant products may be subject to stop-sale orders or penalties under the Essential Commodities Act, 1955. With the increasing regulation and upcoming compliance deadlines, companies must ensure their products meet all technical and legal requirements to remain in the Indian market. Schedule VI is the section of the FCO that provides official specifications and standards for biostimulants in India. It was introduced through the 2021 Amendment to formally regulate biostimulants under Indian fertilizer law (Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare, 2025b).

Table 2. New Biostimulant categories under the FCO Schedule VI (2025)

|

Category

|

Types

|

Key specifications

|

|

Humic & Fulvic acid products

|

Liquid (≥ 6%) Granular (≥ 1.5%) Mixed (25%–76%)

|

TOC %, pH range, solubility, crop specificity, and dosage

|

|

Seaweed extracts

|

Ascophyllum nodosum (7%), Kappaphycus alvarezii (7.2%, 9.5%) Mixed (K. alvarezii + Sargassum swartzii)

|

Alginic/carrageenan content, TOC %, pH, TDS, target crops, dosage

|

|

Botanical extracts

|

Spirulina (10% liquid) Adhatoda vasica (2%)

|

Protein %, specific gravity, pH, solubility, crop guidance

|

|

Mixed biostimulant blends

|

Seaweed + algal Humic + seaweed + amino acids + vitamins Antioxidant powders

|

Multi-component formulations with combined composition and crop/dosage specifications

|

|

Protein hydrolysates & Amino acids

|

Derived from animal hair, soybean, maize Microbial biomass (e.g., vinasse with 18% glutamic acid)

|

TOC %, total amino acids, pH, solubility, dosage, crop-specific use

|

|

Cell-free microbial products

|

Lipo-chitooligosaccharides from E. coli Lipase from S. cerevisiae

|

Active content (IU/mL or mg/L), pH, solubility, dosage for paddy and other crops

|

|

Live microorganisms

|

Methylococcus capsulatus (powdered) Microbial consortium (M. symbioticum + M. extrorquens)

|

CFU counts (colony-forming units), pH, density, solubility, crop-specific dosage

|

|

Biochemicals

|

2-Bromo-(1H)-Indole-3-Carboxaldehyde (1 ppm for tomato)

|

Active ingredient content, TOC, pH, solubility, target crop, dosage

|

|

Tolerance limits

|

Live microbial products under Part B

|

Defined microbial population limits (CFU/mL or g), activity levels, and allowed formulation ranges

|

Source: https://fert.nic.in

CONCLUSION

The growing challenges in modern agriculture such as soil degradation, declining nutrient efficiency, overuse of chemical inputs, and the impacts of climate change have created an urgent need for sustainable alternatives. Biostimulants have emerged as a promising solution to these issues. Unlike conventional fertilizers and pesticides, biostimulants do not directly supply nutrients or kill pests; instead, they work by enhancing the plant's natural physiological processes. They enhance nutrient uptake and efficiency, stimulate root development, strengthen plant responses to abiotic stresses such as drought and salinity, and promote resilience against biotic stresses through improved plant immunity and beneficial microbial activity. Scientific studies have consistently shown that biostimulants such as seaweed extracts, humic and fulvic acids, amino acids and microbial formulations can significantly boost crop yields, improve quality and enhance stress tolerance across various crops and agro-climatic conditions. Their role is vital in sustainable and climate-smart agriculture where reducing environmental harm while maintaining productivity is critical. With increasing regulatory support such as India’s Fertiliser Control Order (FCO) 2021 amendment, which formalized the registration and quality standards for biostimulants, these products are gaining wider acceptance. In conclusion, biostimulants offer a viable path toward more resilient, efficient and eco-friendly agricultural systems and will play a crucial role in future food and environmental security.

REFERENCES

Acadian Plant Health. (2025 ). Acadian launches advanced biostimulant seed treatment for abiotic stress management. Global Agriculture, 2:(10).

Akbar, A., Han, B., Khan, A. H., Feng, C., Ullah, A., Khan, A. S., & Yang, X. (2022). A transcriptomic study reveals salt stress alleviation in cotton plants upon salt tolerant PGPR inoculation. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 200:104928.

Anand, K. V., Eswaran, K., & Ghosh, A. (2018). Life cycle impact assessment of a seaweed product obtained from Gracilaria edulis–A potent plant biostimulant. Journal of Cleaner Production, 170:1621-1627.

Arslan, E., Agar, G., & Aydin, M. (2021). Humic acid as a biostimulant in improving drought tolerance in wheat: The expression patterns of drought-related genes. Plant Molecular Biology Reporter, 39(3):508-519.

Backer, R., Rokem, J. S., Ilangumaran, G., Lamont, J., Praslickova, D., Ricci, E., & Smith, D. L. (2018). Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria: context, mechanisms of action, and roadmap to commercialization of biostimulants for sustainable agriculture. Frontiers in plant science, 9:1473.

Basavaraja, P. K., Yogendra, N. D., Zodape, S. T., Prakash, R., & Ghosh, A. (2018). Effect of seaweed sap as foliar spray on growth and yield of hybrid maize. Journal of Plant Nutrition, 41(14):1851-1861.

Bhupenchandra, I., Chongtham, S. K., Devi, E. L., Choudhary, A. K., Salam, M. D., Sahoo, M. R., & Khaba, C. I. (2022). Role of biostimulants in mitigating the effects of climate change on crop performance. Frontiers in Plant Science, 13:967665.

Birthal, P. S., Hazrana, J., & Negi, D. S. (2021). Impacts of climatic hazards on agricultural growth in India. Climate and Development, 13(10):895-908.

Brown, P., & Saa, S. (2015). Biostimulants in agriculture. Frontiers in plant science, 6:671.

Calvo, P., Nelson, L., & Kloepper, J. W. (2014). Agricultural uses of plant biostimulants. Plant and soil, 383:3-41.

Campbell, B. M., Beare, D. J., Bennett, E. M., Hall-Spencer, J. M., Ingram, J. S., Jaramillo, F., & Shindell, D. (2017). Agriculture production as a major driver of the Earth system exceeding planetary boundaries. Ecology and society, 22(4).

Canellas, L. P., Olivares, F. L., Okorokova-Façanha, A. L., & Façanha, A. R. (2002). Humic acids isolated from earthworm compost enhance root elongation, lateral root emergence, and plasma membrane H⁺-ATPase activity in maize roots. Plant Physiology, 130(4):1951–1957.

Carillo, P., Colla, G., Fusco, G. M., Dell’ Aversana, E., El-Nakhel, C., Giordano, M., & Rouphael, Y. (2019). Morphological and physiological responses induced by protein hydrolysate-based biostimulant and nitrogen rates in greenhouse spinach. Agronomy, 9(8): 450.

Da Silva, A. L., Canteri, M. G., da Silva, A. J., & Bracale, M. F. (2017). Meta-analysis of the application effects of a biostimulant based on extracts of yeast and amino acids on off-season corn yield. Semina: Ciências Agrárias, 38(4):2293-2303.

Ertani, A., Schiavon, M., Muscolo, A., & Nardi, S. (2013). Alfalfa plant-derived biostimulant stimulate short-term growth of salt stressed Zea mays L. plants. Plant and soil, 364:145-158.

FAO. (2023). FAOSTAT Statistical Database. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved from https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/

Gomes, G. A., Pereira, R. A., Sodre, G. A., & Gross, E. (2019). Humic acids from vermin-compost positively influence the nutrient uptake in mangos teen seedlings1. Pesquisa Agropecuária Tropical, 49:55529.

Gupta, S., Stirk, W. A., Plackova, L., Kulkarni, M. G., Dolezal, K., & Van Staden, J. (2021). Interactive effects of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria and a seaweed extract on the growth and physiology of Allium cepa L. (onion). Journal of Plant Physiology, 262:153437.

Hafez, Y., Attia, K., Alamery, S., Ghazy, A., Al-Doss, A., Ibrahim, E., & Abdelaal, K. (2020). Beneficial effects of biochar and chitosan on antioxidative capacity, osmolytes accumulation and anatomical characters of water-stressed barley plants. Agronomy, 10(5):630.

Irani, H., Valizadeh Kaji, B., & Naeini, M. R. (2021). Biostimulant-induced drought tolerance in grapevine is associated with physiological and biochemical changes. Chemical and Biological Technologies in Agriculture, 8:1-13.

Jardin, D., P. (2015). Plant biostimulants: Definition, concept, main categories and regulation. Scientia horticulturae, 196:3-14.

Khan, M. A., Asaf, S., Khan, A. L., Jan, R., Kang, S. M., Kim, K. M., & Lee, I. J. (2020). Extending thermotolerance to tomato seedlings by inoculation with SA1 isolate of Bacillus cereus and comparison with exogenous humic acid application. PLoS One, 15(4):0232228.

Kumar, R., Deka, B. C., Kumawat, N., & Thirugnanavel, A. (2020). Effect of integrated nutrition on productivity, profitability and quality of French bean (Phaseolus vulgaris). Indian Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 90(2):431-5.

Laurent, E. A., Ahmed, N., Durieu, C., Grieu, P., & Lamaze, T. (2020). Marine and fungal biostimulants improve grain yield, nitrogen absorption and allocation in durum wheat plants. The Journal of Agricultural Science, 158(4):279-287.

Mawar, R., Manjunath, B.,L., & Kumar, S. (2021). Commercialization, Diffusion and Adoption of Bioformulations for Sustainable Disease Management in Indian Arid Agriculture: Prospects and Challenges. Circular Economy and Sustainability 1:1367–1385

Mawar, R, Sayyed, R. Z., Sharma, S. K. & Sundari, K. S. (2023). Plant Growth Promoting Microorganisms of Arid Region. Springer Nature Singapore, Pp 455.

Meena, D.C., Birthal, P.S. & Kumara, T.M.K (2025). Biostimulants for sustainable development of agriculture: a bibliometric content analysis. Discov Agric 3, 2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44279-024-00149-5

Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare. (2021a). Fertiliser (Control) Order, 1985, Amendment regarding biostimulants Government of India.

Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare. (2025b). Fertiliser (Control) Order, 1985 – Second Amendment. Government of India.

Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare. (2021c). Gazette Notification on Inclusion of Biostimulants under Fertilizer Control Order (FCO), 1985. Government of India.

Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare. (2021d). Guidelines for Registration of Biostimulants under the Fertilizer Control Order, 1985 (Amended). Government of India.

Mullany, M. (2024). Biostimulants are Variably Effective at Preserving Field Crop Yield Under Water Stress. A Global Meta-Analysis, SSRN 4805504.

Ortiz-Bobea, A., Ault, T. R., Carrillo, C. M., Chambers, R. G., & Lobell, D. B. (2021). Anthropogenic climate change has slowed global agricultural productivity growth. Nature Climate Change, 11(4):306-312.

Petrozza, A., Santaniello, A., Summerer, S., Di Tommaso, G., Di Tommaso, D., Paparelli, E., & Cellini, F. (2014). Physiological responses to Megafol treatments in tomato plants under drought stress: A phenomic and molecular approach. Scientia Horticulturae, 174:185-192.

Povero, G., Mejia, J. F., Di Tommaso, D., Piaggesi, A., & Warrior, P. (2016). A seaweed-based biostimulant (Ascophyllum nodosum) improves tolerance to low temperature stress in tomato plants. Journal of Applied Phycology, 28(4):2551–2561

Power, A. G. (2010). Ecosystem services and agriculture: tradeoffs and synergies. Philosophical transactions of the royal society B: biological sciences, 365(1554):2959-2971.

Rabelo, V. M., Magalhaes, P. C., Bressanin, L. A., Carvalho, D. T., Reis, C. O. D., Karam, D., & Souza, T. C. D. (2019). The foliar application of a mixture of semisynthetic chitosan derivatives induces tolerance to water deficit in maize, improving the antioxidant system and increasing photosynthesis and grain yield. Scientific reports, 9(1):8164.

Rakkammal, K., Maharajan, T., Ceasar, S. A., & Ramesh, M. (2023). Biostimulants and their role in improving plant growth under drought and salinity. Cereal Research Communications, 51(1), 61-74.

Rathore, S. S., Chaudhary, D. R., Boricha, G. N., Ghosh, A., Bhatt, B. P., Zodape, S. T., & Patolia, J. S. (2009). Effect of seaweed extract on the growth, yield and nutrient uptake of soybean (Glycine max) under rainfed conditions. South African Journal of Botany, 75(2):351-355.

Rouphael, Y., Colla, G., Giordano, M., El-Nakhel, C., Kyriacou, M. C., & De Pascale, S. (2017). Foliar applications of a legume-derived protein hydrolysate elicit dose-dependent increases of growth, leaf mineral composition, yield and fruit quality in two greenhouse tomato cultivars. Scientia horticulturae, 226:353-360.

Sharma, H. S., Fleming, C., Selby, C., Rao, J. R., & Martin, T. (2014). Plant biostimulants: a review on the processing of macroalgae and use of extracts for crop management to reduce abiotic and biotic stresses. Journal of applied phycology, 26:465-490.

Singh, I., Anand, K. V., Solomon, S., Shukla, S. K., Rai, R., Zodape, S. T., & Ghosh, A. (2018). Can we not mitigate climate change using seaweed based biostimulant: A case study with sugarcane cultivation in India. Journal of Cleaner Production, 204:992-1003.

Singh, S., Singh, M. K., Pal, S. K., Trivedi, K., Yesuraj, D., Singh, C. S., & Ghosh, A. (2016). Sustainable enhancement in yield and quality of rain-fed maize through Gracilaria edulis and Kappaphycus alvarezii seaweed sap. Journal of applied Phycology, 28:2099-2112.

Suman, S., Spehia, R. S., & Sharma, V. (2017). Humic acid improved efficiency of fertigation and productivity of tomato. Journal of plant nutrition, 40(3):439-446.

Tursun, A. O. (2022). Effect of foliar application of seaweed (organic fertilizer) on yield, essential oil and chemical composition of coriander. Plos one, 17(6):269067.

Van, L. J, Gerrewey, T., & Geelen, D. (2022). A meta-analysis of biostimulant yield effectiveness in field trials. Frontiers in Plant Science, 13:836702.

Van Oosten, M. J., Pepe, O., De Pascale, S., Silletti, S., & Maggio, A. (2017). The role of biostimulants and bioeffectors as alleviators of abiotic stress in crop plants. Chemical and Biological Technologies in Agriculture, 4:1-12.

Yadav, J., & Verma, J. P. (2014). Effect of seed inoculation with indigenous Rhizobium and plant growth promoting rhizobacteria on nutrients uptake and yields of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.). European journal of soil biology, 63:70-77.

Ziomek, S, A., & Szczepanek, M. (2019). Soil extracellular enzyme activities and uptake of N by oilseed rape depending on fertilization and seaweed biostimulant application. Agronomy, 9(9):480.

Natural Boost for Your Crops: The Role of Biostimulants in Smarter, Sustainable Farming

DOI: https://doi.org/10.56669/NECZ9831

ABSTRACT

The exact definition of biostimulants remains debated, with no universal agreement on what should or shouldn’t be included in this category. For example, certain microbes, such as Azotobacter, Rhizobium, and Azospirillum, are considered plant microbial biostimulants in Europe, whereas in India, they are classified as biofertilizers. Both the European Union and India have official definitions for biostimulants; however, countries such as the USA, China, Brazil, and Mexico tend to categorize biostimulants under broader terms, including soil amendments, plant growth regulators, or organic inputs. The most widely accepted definition describes biostimulants as substances, microorganisms, or mixtures of both applied to plants, seeds, or the root zone (rhizosphere) to stimulate the plant's natural processes.

Keywords: Biostiumlants, sustainable farming, biofertilizers, smart agriculture

INTRODUCTION

Biostimulants are made from natural materials such as extracts from plants, seaweed, microbial cultures, organic residues, and other by-products, providing an environmentally safe substitute for synthetic agricultural inputs (Anand et al., 2018; Singh et al., 2018). The 2018 U.S. Farm Bill defines biostimulants as substances or microbes that promote plant growth by enhancing nutrient uptake, efficiency, stress resilience, or yield, including organisms such as Rhizobium, Trichoderma, Bacillus, and Pseudomonas, as long as no pest control claims are made. In Canada, biostimulants are regulated under the Fertilizers Act; however, current rules prevent dual claims for both nutrition and protection. The EU recognizes only four microbial species—Azotobacter, Azospirillum, Rhizobium, and mycorrhizae—excluding microbial consortia. In contrast, India permits consortia under the Fertilizer Control Order (FCO) and enforces separate regulations for biofertilizers and biopesticides. While the U.S. and EU define biostimulants based on plant responses, India focuses on microbial functionality. Globally, definitions vary, with no unified consensus; for instance, microbes considered biostimulants in Europe may be categorized as biofertilizers in India (Mawar et al., 2021; 2023). Both the European Union and India have official definitions for biostimulants; however, countries such as the U.S., China, Brazil, and Mexico tend to categorize biostimulants under broader terms, including soil amendments, plant growth regulators, or organic inputs. The most widely accepted definition describes biostimulants as substances, microorganisms, or mixtures of both, applied to plants, seeds, or the root zone (rhizosphere) to stimulate the plant’s natural processes (Figure 1). This stimulation happens regardless of the product’s nutrient content. It aims to improve one or more of the following: (i) nutrient use efficiency, (ii) tolerance to environmental stresses, (iii) crop yield and quality, and (iv) availability of nutrients in the soil or rhizosphere. (Jardin 2015).

Why was biostimulant needed?

The introduction of high-yielding crop varieties has significantly increased agricultural output and food production. However, these crops require more water and agrochemicals, such as fertilizers and pesticides, to reach their full yield potential. This growing dependence on chemicals and groundwater is causing harm to natural resources, including soil health, water supplies, farm biodiversity, and the environment (Campbell et al., 2017; Power et al., 2010). Moreover, the overuse and careless application of these chemicals have led to a decline in the quality of food and animal feed, which negatively affects human and animal health. Additionally, the benefits from using more fertilizers are decreasing, resulting in slower growth in crop production and higher farming expenses. For example, in developing countries, the annual increase in food grain yields dropped from 1.71% during 1981–2000 to 1.43% during 2001–2020, even though fertilizer use rose from 40 to 55 kg per hectare (FAOSTAT). Climate change poses a serious challenge to the long-term sustainability of farming. Studies estimate that since 1961, climate change has slowed the growth of global agricultural productivity by approximately 21%, with developing countries being the most affected. (Ortiz-Bobea et al., 2021) In India, research shows that despite advances in technology, climate change has reduced agricultural productivity growth by roughly 25% since Birthal et al., 2021). Biostimulants are believed to provide multiple advantages, such as protecting natural resources, helping crops cope with stress from pests and environmental factors, and lowering production cost-all without harming crop yields (Van et al., 2022).

Biostimulants don’t provide nutrients or directly fight pests and diseases. Instead, they activate natural processes inside the plants and the beneficial microbes in the soil (Jardin 2015; Sharma et al.2014). By causing changes at the molecular level and affecting the plant’s physiology, biochemistry, and structure, biostimulants help plants better resist stress caused by pests, diseases, and environmental conditions

IMPACT OF BIOSTIMULANTS

Crop yields and quality traits

Biostimulants enhance plant growth and crop yields by affecting the plant’s natural processes. They promote the development of roots and shoots, increase organic carbon levels, improve nutrient exchange and nitrogen use, stimulate beneficial soil microbes, boost the plant’s antioxidant defenses, and help plants retain water more effectively (Carillo et al., 2019; Arslan et al., 2021). According to a meta-analysis, applying various biostimulants leads to an increase in crop yields ranging from 15% to 17%. Foliar spraying with seaweed extracts from Kappaphycus alvarezii and Gracilaria edulis has been shown to boost maize yields by approximately 18.5% and 26%, respectively (Basavaraja et al., 2018). The use of biostimulants, such as amino acids and yeast extract, resulted in yield increases of 8.5% and 20%, respectively, in off-season corn grown under water-stress conditions (Da Silva et al., 2017). In dry and semi-dry areas, using seaweed extract, humic and fulvic acids, chitosan, and plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) was shown to improve crop yields by 8.5% during moderate water stress and by 11.4% under severe water stress (Mullany M., 2024). Seaweed extract applied at a 15% concentration enhanced maize net returns by between 7.7% and 16.5% (Singh et al., 2016). Additionally, research has shown that biostimulants can enhance the nutritional quality of crops (Suman et al., 2017). Foliar application of seaweed extract derived from Kappaphycus alvarezii significantly improved the nutrient content in soybean grains, increasing nitrogen by 36%, phosphorus by 61%, potassium by 49%, and sulfur by 93% (Rathore et al., 2009). Seaweed-based biostimulants contain natural plant hormones such as auxin, cytokinin, kinetin, zeatin, gibberellins, glycine betaine, and choline chloride. These compounds promote plant growth and help crops withstand environmental stress by speeding up the movement of nutrients from leaves to stems and boosting the production of photosynthetic pigments (Gupta et al., 2021). Therefore, biostimulants play an important role in improving nutritional quality while reducing the use of chemical inputs and lessening harmful environmental impacts.

Nutrient use efficiency (NUE)

The use of biostimulants has been shown to improve nutrient use efficiency (NUE) and reduce the need for fertilizers, lowering production costs (Brown et al., 2015). For instance, applying amino acids like Terramin Pro increased NUE in wheat by 28% (Laurent et al., 2020), while protein hydrolysates boosted it by 12.9% in spinach and seaweed extracts raised it by 16% in rapeseed and wheat (Ziomek et al., 2019). Applying seaweed extracts to maize notably boosted nutrient absorption. Extract from Kappaphycus alvarezii lead to increases of 31% in nitrogen (N), 38% in phosphorus (P), and 28% in potassium (K) uptake. Similarly, Gracilaria edulis extract enhanced N, P, and K uptake by 23%, 41%, and 26%, respectively (Basavaraja et al., 2018). The use of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) enhances nutrient use efficiency by improving nutrient uptake, facilitating nitrogen fixation, and promoting nutrient mobility in the soil, particularly under stress conditions. For instance, inoculating green gram seeds with PGPR led to increased N, P, and K uptake by 17%, 21%, and 23%, respectively, contributing to improved crop productivity (Kumar et al., 2020; Yadav et al., 2014). It is also widely recognized that strong root growth is essential for plants to absorb nutrients effectively. Many studies have found that using biostimulants encourages better root development, enabling plants to explore the soil more thoroughly and take up nutrients more efficiently (Bhupenchandra et al., 2022; Rouphael et al., 2017). Biostimulant application modifies the soil’s microbial structure and enhances enzymatic activity, facilitating faster humus development and improving the soil’s ability to store carbon (Singh et al., 2018). Additionally, biostimulants can improve nutrient availability, uptake, and transport within plants by stimulating H⁺-ATPase enzyme activity. This leads to increased hydrogen ion release from the roots, resulting in a lower pH in the surrounding root zone (Canellas et al., 2002).

Response to abiotic stress

Biostimulants help plants become more resistant or tolerant to environmental stresses like drought. Acadian Plant Health has introduced ASM, an advanced seed treatment that offers dual protection by enhancing resistance to both biotic stresses (pests and diseases) and abiotic stresses like drought, heat, and cold (Figure 2). It combines Acadian’s proprietary seaweed extract with a synergistic active ingredient to strengthen early plant development. ASM enhances root and shoot growth, enabling crops to tolerate environmental stress better. A yield increase of up to 16% in maize under drought, 28–35% more root biomass in soybeans, and a yield increase of up to 16% in maize under drought, as well as a yield improvement of up to 6.4% across regions (Acadian Plant Health, 2025). In wheat and corn, ASM also activated stress-response genes, confirming its effectiveness at the molecular level. Importantly, it showed no negative impact on germination or seedling uniformity, ensuring safe and reliable early crop performance (Acadian Plant Health, 2025). Research has shown that biostimulants protect crops such as maize (Ertani et al., 2013), tomato (Petrozza et al., 2014), wheat, and other horticultural plants (Irani et al., 2021) from drought stress. Seaweed extracts help plants use water more efficiently and increase crop production during drought stress (Bhupenchandra et al., 2022). Further, humic acid has been shown to help tomatoes and bell peppers tolerate heat stress (Gomes et al., 2019). Seaweed extracts have been found to reduce the impact of nutrient deficiencies during cold weather (Van et al., 2017; Tursun, 2022). Similarly, other research indicates that biostimulants can help plants cope with challenges such as low rainfall and extreme temperature conditions. Salinity stress is a big problem for farming, especially in dry, semi-dry, and coastal areas. Spraying biostimulants, such as humic acid, glycine betaine, and chitosan, on leaves helps mitigate the harmful effects of salt stress in crops like wheat, maize, and barley. Biostimulants enhance photosynthetic efficiency and improve plant water relations by regulating stomatal conductance, maintaining leaf relative water content, and improving cellular osmotic adjustment. (Rakkammal et al., 2023; Meena et al., 2025). They also reduce cell damage, increase protective compounds like proline, lower harmful molecules called reactive oxygen species (ROS) and improve antioxidant enzyme activity (Figure 2). All these effects help plants better handle stress from their environment (Rabelo et al., 2019; Hafez et al., 2020). Biostimulants help plants cope with environmental stress by triggering the production of protective compounds like heat shock proteins, phenolics, amino acids, organic acids, dehydrins, and ACC-deaminase. Application of humic acid and seaweed extract has been shown to activate drought-responsive genes, enhancing photosynthetic efficiency, improving water retention capacity, and optimizing stomatal regulation under drought stress conditions (Khan et al., 2020).

Response to biotic stress

Biostimulants play a crucial role in enhancing plant resistance to biotic stresses by activating innate defense mechanisms and strengthening host–pathogen interactions. They stimulate the synthesis of defense-related compounds such as phenolics, heat shock proteins, amino acids, organic acids, dehydrins, and enzymes associated with induced systemic resistance (ISR), including ACC-deaminase, which helps regulate stress-induced ethylene levels. Microbial biostimulants, particularly Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus pumilus, have been shown to enhance plant tolerance to pathogen attack by modulating key metabolic pathways such as ascorbate–aldarate metabolism, glyoxylate and dicarboxylate cycles, and sugar transformation processes, thereby improving cellular redox balance and defense readiness (Akbar et al., 2022). Biostimulants also improve rhizosphere health by promoting beneficial microbial communities that compete with or suppress phytopathogens through mechanisms such as antibiosis, competition for nutrients and space, and mycoparasitism. Widely used microbial biostimulants, including Trichoderma spp., Bacillus subtilis, and Pseudomonas fluorescens, act as effective biological antagonists against soil- and foliar-borne pathogens while simultaneously enhancing root architecture, nutrient uptake, and plant vigor (Backer et al., 2018). In addition, non-microbial biostimulants such as seaweed extracts and chitosan function as elicitors of plant defense, triggering systemic acquired resistance (SAR) and reinforcing cell wall integrity, thereby reducing pathogen penetration and colonization. Other inputs, including silicon and protein hydrolysates, further strengthen physical and biochemical barriers by enhancing lignification, enzyme activity, and overall metabolic efficiency, leading to improved disease resistance (Table 1). For optimal disease suppression, biostimulants are most effective when applied preventively, prior to pathogen establishment, and are increasingly integrated into holistic pest and disease management strategies as sustainable alternatives or complements to chemical control measures (Calvo et al., 2014; Povero et al., 2016).

Table 1. Examples of biostimulants for biotic stresses

Type

Examples

Mode of action

Microbial biostimulants

Trichoderma spp., Bacillus subtilis, P. fluorescens

Antagonize pathogens, trigger ISR

Seaweed extracts

Ascophyllum nodosum, Ecklonia maxima

Contain bioactive compounds that boost immunity

Protein hydrolysates

Enzymatically hydrolyzed soy and animal proteins

Improve metabolic activity and stress tolerance

Chitosan

Derived from crustacean shells

Triggers SAR, strengthens cell walls

Silicon

Potassium silicate, sodium silicate

Reinforces cell walls, primes defense responses

How biostimulants work against biotic stresses: Biostimulants play a vital role in helping crops combat biotic stresses by enhancing natural plant defenses and improving overall plant health. They can induce systemic resistance by activating immune responses such as Systemic Acquired Resistance (SAR) or Induced Systemic Resistance (ISR), making plants more resilient to pathogen attacks (Figure 2). Biostimulants also enhance the soil microbiome by promoting beneficial microbes that can out compete harmful pathogens. Moreover, they help reduce oxidative stress by increasing antioxidant levels, which protects plant cells from damage during infection, for example, in rice, products like Chitoplant (chitosan) and Biozyme® (seaweed + amino acids) enhance immunity and root development, while Trichoderma viride controls fungal diseases. In tomatoes, Actosol® (humic acid) strengthens roots, Neemazal manages pests, and Biovita boosts resistance. Trichoderma harzianum is used for root disease prevention. For grapes, Kelpak® and chitosan sprays reduce fungal infections, and Bacillus subtilis protects leaves. In maize, Fulvital (fulvic acid) improves nutrient uptake, Bioguard (Bacillus spp.) protects roots, and AminoX aids plant recovery. These biostimulants offer a natural way to manage crop diseases effectively.

Factors affecting the effectiveness of biostimulant: The effectiveness of biostimulants in agriculture is influenced by several factors, including plant-related, environmental, and biostimulant-specific variables. Plant factors like species, growth stage, health status, and genetic makeup determine responsiveness, with stressed or nutrient-deficient plants often being more sensitive. The plant’s developmental stage such as seedling, vegetative, flowering, or fruiting also influences its need for biostimulants. Environmental factors such as soil type, pH, temperature, and light intensity are crucial, as they affect nutrient retention, microbial activity, and biostimulant performance. Extreme weather conditions or abiotic stresses like drought or salinity can enhance biostimulant effectiveness in certain cases. Biostimulant-related factors like formulation quality, concentration, application method, and frequency are also key to maximizing benefits. Proper formulation, dosage, and methods of application whether foliar spray, soil drench, or seed treatment are necessary for optimal absorption and distribution. Ultimately, when utilizing microbial biostimulants, the soil microbiome, competition from native microbes, and compatibility with soil conditions can either enhance or mitigate microbial performance. Adding synergistic substances, such as organic matter, can further enhance microbial survival and efficiency, enabling biostimulants to achieve their full potential in boosting plant growth and resilience.

Development of Biostimulants: The development of biostimulants involves a systematic process of identifying, formulating, and testing substances or microorganisms that enhance plant growth, nutrient efficiency, and stress tolerance, without being classified as fertilizers or pesticides. It begins with the identification of potential active ingredients from natural sources such as seaweeds, plant extracts, microbial strains (e.g., Bacillus, Azospirillum), humic substances, amino acids, or other organic compounds. These sources are screened in laboratory conditions for their ability to improve plant physiological processes like nutrient uptake, root development, photosynthesis, or resistance to abiotic stresses such as drought, salinity, and heat (Jardin., 2015). Once promising candidates are identified, formulation development follows. This step focuses on creating a stable, user-friendly product with consistent efficacy. It involves optimizing the concentration of active ingredients, selecting suitable carriers or additives, and determining the most effective form of application (e.g., foliar spray, soil drench, seed coating). During this stage, compatibility with fertilizers and other agrochemicals is also evaluated to ensure the product can be integrated into standard agricultural practices (Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, 2021c).

In India, the registration of biostimulants is governed by the Fertilizer Control Order (FCO), 1985, which was amended in 2021 to include biostimulants as a recognized category. The process begins with the classification of the biostimulant into one of the approved categories such as botanical extracts, seaweed extracts, humic substances, amino acids, or microbial formulations. Manufacturers must first apply for provisional registration by submitting Form G-1, which includes details about the product's composition, manufacturing process, and a certificate of analysis (CoA). Additionally, field trial data from at least two locations demonstrating the product's efficacy must be provided. Provisional registration is typically valid for two years, during which time further studies are conducted. To obtain final registration, manufacturers must submit Form G-2 along with a comprehensive dossier that includes detailed chemical composition, toxicological studies, bio-efficacy trials conducted across different agro-climatic zones, and analyses for heavy metals and pesticide residues. These studies must adhere to the OECD guidelines and be conducted at GLP-certified laboratories. Once the product meets all regulatory requirements and passes the necessary trials, it is granted final registration, allowing for commercialization. The product’s label claims, such as improved plant growth or stress tolerance, must be backed by scientific evidence. Regulatory fees are applicable for both provisional and final registration, and these can vary. The process is overseen by the Department of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, with evaluations conducted by the Central Biostimulant Committee. After registration, the product can be marketed across India, offering farmers sustainable solutions to enhance crop productivity and resilience (Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, 2021d).

Commercialization of biostimulants: The commercialization of biostimulants involves taking a scientifically validated and registered product to market with a focus on production, distribution, and farmer adoption. After regulatory approval, manufacturers scale up production with strict quality control to ensure consistency. Target crops and regions are identified where the product can address specific farming challenges, such as poor growth or stress conditions. Field trials and demonstrations help build trust by showing clear results under real farming conditions. Effective marketing highlights the product’s benefits and returns on investment, while distribution is handled through agri-input dealers, cooperatives, and digital platforms. Farmer training and support further drive adoption. Successful commercialization depends on scientific credibility, strategic outreach, and strong farmer engagement.

Legislations related biostimulants: In India, biostimulants are regulated under the Fertiliser (Control) Order, 1985 (FCO), which was amended in February 2021 to formally define and include biostimulants as a distinct category of agricultural inputs. The amendment introduced Clause 20C (which lays down the process for registration), Clause 38A (for the establishment of a Central Biostimulant Committee), and a new Schedule VI which contains detailed specifications for various types of biostimulants such as humic acid, seaweed extract, amino acid formulations, microbial products, and more (Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare, 2021a).

To market a biostimulant, companies must follow a two-step regulatory process. Initially, a provisional registration can be obtained by submitting Form G, which includes composition details, lab test reports, acute toxicity and eco-toxicity data, bio-efficacy trials in at least two agro-climatic zones, and validated analytical methods. Companies using this route must comply with the latest deadline as per the Second Amendment Order, 2025. Final approval and permanent inclusion in Schedule VI require the submission and review of complete data by the Central Biostimulant Committee. Approved products must meet strict contaminant limits identical to European Union (EU) standards—for example, limits for Pb (120 mg/kg), Cd (1.5 mg/kg), and As (40 mg/kg). Labels must clearly display the product name, composition, application rate, claimed benefits, and a disclaimer noting approval under the FCO. Enforcement is carried out by state fertilizer inspectors and notified testing laboratories. Non-compliant products may be subject to stop-sale orders or penalties under the Essential Commodities Act, 1955. With the increasing regulation and upcoming compliance deadlines, companies must ensure their products meet all technical and legal requirements to remain in the Indian market. Schedule VI is the section of the FCO that provides official specifications and standards for biostimulants in India. It was introduced through the 2021 Amendment to formally regulate biostimulants under Indian fertilizer law (Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare, 2025b).

Table 2. New Biostimulant categories under the FCO Schedule VI (2025)

Category

Types

Key specifications

Humic & Fulvic acid products

Liquid (≥ 6%) Granular (≥ 1.5%) Mixed (25%–76%)

TOC %, pH range, solubility, crop specificity, and dosage

Seaweed extracts

Ascophyllum nodosum (7%), Kappaphycus alvarezii (7.2%, 9.5%) Mixed (K. alvarezii + Sargassum swartzii)

Alginic/carrageenan content, TOC %, pH, TDS, target crops, dosage

Botanical extracts

Spirulina (10% liquid) Adhatoda vasica (2%)

Protein %, specific gravity, pH, solubility, crop guidance

Mixed biostimulant blends

Seaweed + algal Humic + seaweed + amino acids + vitamins Antioxidant powders

Multi-component formulations with combined composition and crop/dosage specifications

Protein hydrolysates & Amino acids

Derived from animal hair, soybean, maize Microbial biomass (e.g., vinasse with 18% glutamic acid)

TOC %, total amino acids, pH, solubility, dosage, crop-specific use

Cell-free microbial products

Lipo-chitooligosaccharides from E. coli Lipase from S. cerevisiae

Active content (IU/mL or mg/L), pH, solubility, dosage for paddy and other crops

Live microorganisms

Methylococcus capsulatus (powdered) Microbial consortium (M. symbioticum + M. extrorquens)

CFU counts (colony-forming units), pH, density, solubility, crop-specific dosage

Biochemicals

2-Bromo-(1H)-Indole-3-Carboxaldehyde (1 ppm for tomato)

Active ingredient content, TOC, pH, solubility, target crop, dosage

Tolerance limits

Live microbial products under Part B

Defined microbial population limits (CFU/mL or g), activity levels, and allowed formulation ranges

Source: https://fert.nic.in

CONCLUSION

The growing challenges in modern agriculture such as soil degradation, declining nutrient efficiency, overuse of chemical inputs, and the impacts of climate change have created an urgent need for sustainable alternatives. Biostimulants have emerged as a promising solution to these issues. Unlike conventional fertilizers and pesticides, biostimulants do not directly supply nutrients or kill pests; instead, they work by enhancing the plant's natural physiological processes. They enhance nutrient uptake and efficiency, stimulate root development, strengthen plant responses to abiotic stresses such as drought and salinity, and promote resilience against biotic stresses through improved plant immunity and beneficial microbial activity. Scientific studies have consistently shown that biostimulants such as seaweed extracts, humic and fulvic acids, amino acids and microbial formulations can significantly boost crop yields, improve quality and enhance stress tolerance across various crops and agro-climatic conditions. Their role is vital in sustainable and climate-smart agriculture where reducing environmental harm while maintaining productivity is critical. With increasing regulatory support such as India’s Fertiliser Control Order (FCO) 2021 amendment, which formalized the registration and quality standards for biostimulants, these products are gaining wider acceptance. In conclusion, biostimulants offer a viable path toward more resilient, efficient and eco-friendly agricultural systems and will play a crucial role in future food and environmental security.

REFERENCES

Acadian Plant Health. (2025 ). Acadian launches advanced biostimulant seed treatment for abiotic stress management. Global Agriculture, 2:(10).

Akbar, A., Han, B., Khan, A. H., Feng, C., Ullah, A., Khan, A. S., & Yang, X. (2022). A transcriptomic study reveals salt stress alleviation in cotton plants upon salt tolerant PGPR inoculation. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 200:104928.

Anand, K. V., Eswaran, K., & Ghosh, A. (2018). Life cycle impact assessment of a seaweed product obtained from Gracilaria edulis–A potent plant biostimulant. Journal of Cleaner Production, 170:1621-1627.

Arslan, E., Agar, G., & Aydin, M. (2021). Humic acid as a biostimulant in improving drought tolerance in wheat: The expression patterns of drought-related genes. Plant Molecular Biology Reporter, 39(3):508-519.

Backer, R., Rokem, J. S., Ilangumaran, G., Lamont, J., Praslickova, D., Ricci, E., & Smith, D. L. (2018). Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria: context, mechanisms of action, and roadmap to commercialization of biostimulants for sustainable agriculture. Frontiers in plant science, 9:1473.

Basavaraja, P. K., Yogendra, N. D., Zodape, S. T., Prakash, R., & Ghosh, A. (2018). Effect of seaweed sap as foliar spray on growth and yield of hybrid maize. Journal of Plant Nutrition, 41(14):1851-1861.

Bhupenchandra, I., Chongtham, S. K., Devi, E. L., Choudhary, A. K., Salam, M. D., Sahoo, M. R., & Khaba, C. I. (2022). Role of biostimulants in mitigating the effects of climate change on crop performance. Frontiers in Plant Science, 13:967665.

Birthal, P. S., Hazrana, J., & Negi, D. S. (2021). Impacts of climatic hazards on agricultural growth in India. Climate and Development, 13(10):895-908.

Brown, P., & Saa, S. (2015). Biostimulants in agriculture. Frontiers in plant science, 6:671.

Calvo, P., Nelson, L., & Kloepper, J. W. (2014). Agricultural uses of plant biostimulants. Plant and soil, 383:3-41.

Campbell, B. M., Beare, D. J., Bennett, E. M., Hall-Spencer, J. M., Ingram, J. S., Jaramillo, F., & Shindell, D. (2017). Agriculture production as a major driver of the Earth system exceeding planetary boundaries. Ecology and society, 22(4).

Canellas, L. P., Olivares, F. L., Okorokova-Façanha, A. L., & Façanha, A. R. (2002). Humic acids isolated from earthworm compost enhance root elongation, lateral root emergence, and plasma membrane H⁺-ATPase activity in maize roots. Plant Physiology, 130(4):1951–1957.

Carillo, P., Colla, G., Fusco, G. M., Dell’ Aversana, E., El-Nakhel, C., Giordano, M., & Rouphael, Y. (2019). Morphological and physiological responses induced by protein hydrolysate-based biostimulant and nitrogen rates in greenhouse spinach. Agronomy, 9(8): 450.

Da Silva, A. L., Canteri, M. G., da Silva, A. J., & Bracale, M. F. (2017). Meta-analysis of the application effects of a biostimulant based on extracts of yeast and amino acids on off-season corn yield. Semina: Ciências Agrárias, 38(4):2293-2303.

Ertani, A., Schiavon, M., Muscolo, A., & Nardi, S. (2013). Alfalfa plant-derived biostimulant stimulate short-term growth of salt stressed Zea mays L. plants. Plant and soil, 364:145-158.

FAO. (2023). FAOSTAT Statistical Database. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved from https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/

Gomes, G. A., Pereira, R. A., Sodre, G. A., & Gross, E. (2019). Humic acids from vermin-compost positively influence the nutrient uptake in mangos teen seedlings1. Pesquisa Agropecuária Tropical, 49:55529.

Gupta, S., Stirk, W. A., Plackova, L., Kulkarni, M. G., Dolezal, K., & Van Staden, J. (2021). Interactive effects of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria and a seaweed extract on the growth and physiology of Allium cepa L. (onion). Journal of Plant Physiology, 262:153437.

Hafez, Y., Attia, K., Alamery, S., Ghazy, A., Al-Doss, A., Ibrahim, E., & Abdelaal, K. (2020). Beneficial effects of biochar and chitosan on antioxidative capacity, osmolytes accumulation and anatomical characters of water-stressed barley plants. Agronomy, 10(5):630.

Irani, H., Valizadeh Kaji, B., & Naeini, M. R. (2021). Biostimulant-induced drought tolerance in grapevine is associated with physiological and biochemical changes. Chemical and Biological Technologies in Agriculture, 8:1-13.

Jardin, D., P. (2015). Plant biostimulants: Definition, concept, main categories and regulation. Scientia horticulturae, 196:3-14.

Khan, M. A., Asaf, S., Khan, A. L., Jan, R., Kang, S. M., Kim, K. M., & Lee, I. J. (2020). Extending thermotolerance to tomato seedlings by inoculation with SA1 isolate of Bacillus cereus and comparison with exogenous humic acid application. PLoS One, 15(4):0232228.

Kumar, R., Deka, B. C., Kumawat, N., & Thirugnanavel, A. (2020). Effect of integrated nutrition on productivity, profitability and quality of French bean (Phaseolus vulgaris). Indian Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 90(2):431-5.

Laurent, E. A., Ahmed, N., Durieu, C., Grieu, P., & Lamaze, T. (2020). Marine and fungal biostimulants improve grain yield, nitrogen absorption and allocation in durum wheat plants. The Journal of Agricultural Science, 158(4):279-287.

Mawar, R., Manjunath, B.,L., & Kumar, S. (2021). Commercialization, Diffusion and Adoption of Bioformulations for Sustainable Disease Management in Indian Arid Agriculture: Prospects and Challenges. Circular Economy and Sustainability 1:1367–1385

Mawar, R, Sayyed, R. Z., Sharma, S. K. & Sundari, K. S. (2023). Plant Growth Promoting Microorganisms of Arid Region. Springer Nature Singapore, Pp 455.

Meena, D.C., Birthal, P.S. & Kumara, T.M.K (2025). Biostimulants for sustainable development of agriculture: a bibliometric content analysis. Discov Agric 3, 2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44279-024-00149-5

Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare. (2021a). Fertiliser (Control) Order, 1985, Amendment regarding biostimulants Government of India.

Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare. (2025b). Fertiliser (Control) Order, 1985 – Second Amendment. Government of India.

Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare. (2021c). Gazette Notification on Inclusion of Biostimulants under Fertilizer Control Order (FCO), 1985. Government of India.

Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare. (2021d). Guidelines for Registration of Biostimulants under the Fertilizer Control Order, 1985 (Amended). Government of India.

Mullany, M. (2024). Biostimulants are Variably Effective at Preserving Field Crop Yield Under Water Stress. A Global Meta-Analysis, SSRN 4805504.

Ortiz-Bobea, A., Ault, T. R., Carrillo, C. M., Chambers, R. G., & Lobell, D. B. (2021). Anthropogenic climate change has slowed global agricultural productivity growth. Nature Climate Change, 11(4):306-312.

Petrozza, A., Santaniello, A., Summerer, S., Di Tommaso, G., Di Tommaso, D., Paparelli, E., & Cellini, F. (2014). Physiological responses to Megafol treatments in tomato plants under drought stress: A phenomic and molecular approach. Scientia Horticulturae, 174:185-192.

Povero, G., Mejia, J. F., Di Tommaso, D., Piaggesi, A., & Warrior, P. (2016). A seaweed-based biostimulant (Ascophyllum nodosum) improves tolerance to low temperature stress in tomato plants. Journal of Applied Phycology, 28(4):2551–2561

Power, A. G. (2010). Ecosystem services and agriculture: tradeoffs and synergies. Philosophical transactions of the royal society B: biological sciences, 365(1554):2959-2971.

Rabelo, V. M., Magalhaes, P. C., Bressanin, L. A., Carvalho, D. T., Reis, C. O. D., Karam, D., & Souza, T. C. D. (2019). The foliar application of a mixture of semisynthetic chitosan derivatives induces tolerance to water deficit in maize, improving the antioxidant system and increasing photosynthesis and grain yield. Scientific reports, 9(1):8164.

Rakkammal, K., Maharajan, T., Ceasar, S. A., & Ramesh, M. (2023). Biostimulants and their role in improving plant growth under drought and salinity. Cereal Research Communications, 51(1), 61-74.

Rathore, S. S., Chaudhary, D. R., Boricha, G. N., Ghosh, A., Bhatt, B. P., Zodape, S. T., & Patolia, J. S. (2009). Effect of seaweed extract on the growth, yield and nutrient uptake of soybean (Glycine max) under rainfed conditions. South African Journal of Botany, 75(2):351-355.

Rouphael, Y., Colla, G., Giordano, M., El-Nakhel, C., Kyriacou, M. C., & De Pascale, S. (2017). Foliar applications of a legume-derived protein hydrolysate elicit dose-dependent increases of growth, leaf mineral composition, yield and fruit quality in two greenhouse tomato cultivars. Scientia horticulturae, 226:353-360.

Sharma, H. S., Fleming, C., Selby, C., Rao, J. R., & Martin, T. (2014). Plant biostimulants: a review on the processing of macroalgae and use of extracts for crop management to reduce abiotic and biotic stresses. Journal of applied phycology, 26:465-490.

Singh, I., Anand, K. V., Solomon, S., Shukla, S. K., Rai, R., Zodape, S. T., & Ghosh, A. (2018). Can we not mitigate climate change using seaweed based biostimulant: A case study with sugarcane cultivation in India. Journal of Cleaner Production, 204:992-1003.

Singh, S., Singh, M. K., Pal, S. K., Trivedi, K., Yesuraj, D., Singh, C. S., & Ghosh, A. (2016). Sustainable enhancement in yield and quality of rain-fed maize through Gracilaria edulis and Kappaphycus alvarezii seaweed sap. Journal of applied Phycology, 28:2099-2112.

Suman, S., Spehia, R. S., & Sharma, V. (2017). Humic acid improved efficiency of fertigation and productivity of tomato. Journal of plant nutrition, 40(3):439-446.

Tursun, A. O. (2022). Effect of foliar application of seaweed (organic fertilizer) on yield, essential oil and chemical composition of coriander. Plos one, 17(6):269067.

Van, L. J, Gerrewey, T., & Geelen, D. (2022). A meta-analysis of biostimulant yield effectiveness in field trials. Frontiers in Plant Science, 13:836702.

Van Oosten, M. J., Pepe, O., De Pascale, S., Silletti, S., & Maggio, A. (2017). The role of biostimulants and bioeffectors as alleviators of abiotic stress in crop plants. Chemical and Biological Technologies in Agriculture, 4:1-12.

Yadav, J., & Verma, J. P. (2014). Effect of seed inoculation with indigenous Rhizobium and plant growth promoting rhizobacteria on nutrients uptake and yields of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.). European journal of soil biology, 63:70-77.

Ziomek, S, A., & Szczepanek, M. (2019). Soil extracellular enzyme activities and uptake of N by oilseed rape depending on fertilization and seaweed biostimulant application. Agronomy, 9(9):480.